Headlines

Unconquered And Unconquerable: Chief Of Change

“Tishomingo was probably the epitome of who we are today as Chickasaw people. He was adjustable.”

This story was republished with permission by The Meek School of Journalism and New Media at Ole Miss, publishers of “Unconquered and Unconquerable: The Amazing Journey of the Chickasaw Nation.”

In the early 1800s, as the tidal wave of new settlers into Mississippi swelled almost daily, the legendary Chief Tishomingo found white traders selling liquor on Chickasaw land.

Faced with a violation of federal law and the tribe’s treaties, the chief took immediate action. He confiscated the liquor and sold it.

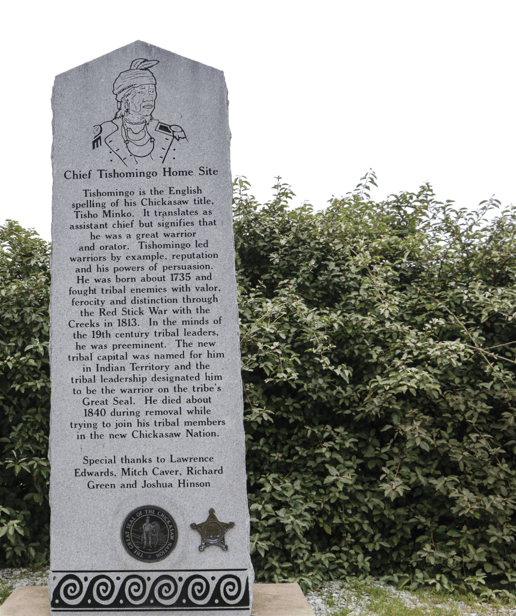

The local sheriff responded by throwing Tishomingo into jail. Court records show the chief was fined $500 for doing what he thought was his job. “Whiskey salesmen came to tribal land and tried to sell whiskey without a permit,” Joe Thomas, special assistant to the Chickasaw Secretary of Culture and Humanities, said as he pondered a monument to the chief between Pontotoc and Tupelo.

This collision between tribal and state authorities illustrates the difficulties the last of the tribe’s full-blooded chiefs encountered at a time when the Chickasaw were brutally squeezed by societal change.

The incessant pressure did not relent until the tribe left Mississippi, forced to relocate west to Oklahoma. Tishomingo would accompany his tribe on the Trail of Tears to their new home but wouldn’t live to finish the journey.

Exact dates and details surrounding Tishomingo’s life are often disputed. A commonly held belief is that he contracted smallpox and died around 1840 at the age of 100 en route to Oklahoma. No one can dispute, however, that he greatly influenced the Chickasaw people during the century he strode the red clay hills of North Mississippi.

When Tishomingo was born around 1740, the tribe was already undergoing major changes within Chickasaw society and in their day-to-day lives.

LaDonna Brown, Chickasaw Nation’s tribal anthropologist, said Tishomingo understood the Chickasaw people, their societal organization, and the importance of spirituality within the tribe in those turbulent times.

“Tishomingo was probably the epitome of who we are today as Chickasaw people,” Brown said. “He was adjustable, he could adjust to different situations.”

The tribe was in the midst of a cultural revolution, especially involving trade and material goods. The old deer skin and pottery trade had given way to farming and business. Tishomingo adjusted with the times, but made sure that his people retained as much as possible of their way of life.

“It didn’t change our culture,” Brown said. “In a time where you think that material items would change a group of people, it definitely didn’t change our identity and we see that in some ways it did reinforce who we are as Chickasaw people.”

A good warrior and a good administrator, Tishomingo won the hearts of Chickasaws and Americans alike.

“He was a good farmer. He had a lot of cotton and corn. He knew times were changing and embraced that change by siding with the Americans,” said William Brekeen, a cultural interpreter for the Chickasaws’ Tupelo Homeland Affairs office.

That’s Tishomingo’s face staring back at you from the Great Seal of the Chickasaw Nation.

Tishomingo worked closely with President George Washington, who awarded the chief a silver medal, and General Andrew Jackson. He served with distinction in the United States military, leading bands of warriors at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, the Red Stick Creek War, and the War of 1812, fighting alongside white men who would eventually push his people from their Mississippi homeland.

Brown tells a heart-tugging story about Tishomingo’s death. The same unconfirmed story appeared in The Commercial Appeal sometime after Tishomingo’s death, recounting how Tishomingo’s daughter sought to ensure her father had a burial worthy of a Chickasaw chief. The source for the story, a man who claimed to have witnessed the events, said that the daughter begged U.S. Army officers for help, saying the family couldn’t afford gunpowder to fire shots over the grave.

The officers provided a coffin. Six soldiers carried Tishomingo to his final resting place. Another six men fired six volleys over the chief’s grave at a sunset ceremony.

The following day, the grateful daughter sought to thank the commanding officer and wound up passing a soiled and worn piece of parchment to the captain of the guard.

It stunned those who saw it. It was Tishomingo’s commission in the U.S. Army, signed by the commander in chief, George Washington.

Today, more than a century and a half after his passing, Tishomingo is revered by the Chickasaw people. His image stares out at the world from the Great Seal of the Chickasaw Nation, his name graces counties and cities in Mississippi and Oklahoma, and memorials for him are scattered through the South, including one at his rural home site a few minutes from Tupelo.

Historians and tribal members continue to research and document details of his life. It’s not always easy because the tribe in that era rarely wrote anything down; history and stories were passed from generation to generation by word of mouth. But sometimes, research pays off and they discover new information.

“Chief is actually a European title the Chickasaws didn’t take on,” Joe Williams of Homeland Affairs said. The name Tishomingo, it turns out, is actually a title. “Minko” means leader and “tisho” means speaker for.

That’s why the nation now refers to Tishomingo as Tishominko. The literal translation is “assistant leader.” Although he was the sole chief of Tishu Miko, one of three districts of the Chickasaw Nation, Tishomingo reported to King Ishtehotopih as the chief officer and held influence over the chiefs of other districts.

By Lana Ferguson. Photography by Ariel Cobbert.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Ariel Cobbert, Mrudvi Bakshi, Taylor Bennett, Lana Ferguson, SECOND ROW: Tori Olker, Josie Slaughter, Kate Harris, Zoe McDonald, Anna McCollum,

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…

viraltrench

February 29, 2020 at 5:56 am

This is so fun! What a great idea. Also I love how authentic you seem to be.