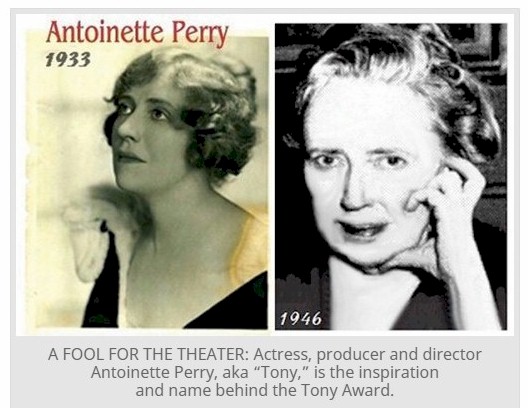

The Tony Award is Broadway’s most coveted prize. But who’s this Tony? The awards, presented by the American Theatre Wing and Broadway League, got their moniker by honoring an indefatigable actress who segued to top producer and director—Antoinette Perry. In a Broadway season of amazing diversity, especially among women creatives, it’s an apt time to remember her contributions at an era when theater was male-dominated.

In 1900, the Denver socialite and beauty, nicknamed Toni, captured Broadway. Ten years into her career, she left it behind to wed hometown beau Frank Frueauff, founder of what became CITGO Petroleum Company. They honeymooned the world; then, at home on Fifth Avenue, entertained like robber barons. Eleven years into their marriage, with two daughters, Miss Perry couldn’t resist theater’s siren call and returned to acting.

In 1922, Frueauff died of a heart attack, leaving a $13-million estate but no will. After a long court battle, his widow was awarded nine million – nonetheless, a fortune at the time.

“Mother was maternal to everyone,” stated late daughter Margaret Perry, a former actress. “It didn’t matter if you were the taxi driver, theatre janitor, or on that pedestal of pedestals, an actor, she was eager to help those in need.”

One of her mother’s trademarks was a huge pocket book, as she called it, slung over her right arm. “In good times and bad, it was always open and she never expected to be repaid. Still, we lived an extravagant life.”

However, Miss Perry felt unfulfilled. She said, “Should I go on playing bridge and dining, going in the same old monotonous circle? It’s easy that way, but it’s a sort of suicide.”

Beginning in 1924, she starred in dramas and comedies by Zona Gale, George Kaufman and Edna Ferber, and William S. Gilbert (of Gilbert and Sullivan), and as Clytemnestra in Sophocles’ Electra, produced and directed by the pioneering Margaret Anglin.

In 1927, after a stroke’s debilitating effects paralyzed her face’s left side, she fell into a depression. Her admiration of Miss Anglin and actress/playwright Rachel Crothers, who directed her own plays, led Miss Perry in a new direction. She partnered with press agent-turned-producer Brock Pemberton as his “angel” for Miss Gale’s 1928 comedy Miss Lulu Bett, which won the Pulitzer Prize.

The duo joined forces as co-producers and co-directors, and fueled gossip lunching daily at Sardi’s. “However, at day’s end,” recalled Margaret, “Mother came home and ‘Uncle’ Brock, as we were instructed to call him, headed to his wife.”

The team struck pay dirt again in 1929 with Preston Sturges’ Strictly Dishonorable, a cynical play about virtue and Prohibition. Movie rights were sold. A month later, the stock market crashed. “Mother awoke two million dollars in debt,” recalled Margaret. “It took seven years to recover.”

As a result of the stroke and financial stress, Miss Perry tired to a debilitating degree. A devout Christian Scientist, she refused to see doctors. “She’d have dinner, read scripts, and supervise our schoolwork,” said Margaret. “Promptly at nine, Brock would phone and they’d talk for hours.”

In 1934, as solo director, she and Pemberton had another hit with Lawrence Riley’s satire, Personal Appearance, about a movie star who falls for a mechanic while on a tour [later adapted into the film Go West, Young Man, starring Mae West].

According to peers, Miss Perry felt a responsibility to audiences. She said, “A theatrical performance is one of the few things the public pays for in advance, sight unseen. We must give them quality entertainment.”

She was the rare female among male power brokers, but no one ever criticized for being strict, professional, and female.

In one month in 1937, she directed (and co-produced) three Pemberton productions, “sometimes rehearsing in our living room,” says Margaret, “while peeling peaches for preserves.” With the introduction of Toni Home Permanent products, Miss Perry altered her nickname to Tony.

In 1938, Claire Booth delivered the blockbuster, Kiss the Boys Goodbye, a spoof dripping with magnolias about producer David O. Selznick’s search for Scarlett O’Hara. Black actor, Frank Wilson, played the butler. In Washington for the pre-Broadway tryout and while scenery was being installed, the company rehearsed at the Willard Hotel across from the White House. When Wilson, who’d been forced to stay elsewhere because of segregation, arrived the doorman wouldn’t allow him to enter. He’d have to use the service entrance.

Though she maintained a lady-like exterior, Miss Perry’s persona was one which didn’t mind ruffling feathers. Blacks were limited to stereotypical roles, but she gave them equal treatment and pay. She was incensed and raised quite a ruckus with management. Thereafter, Wilson entered through the front.

In 1940, Miss Perry, with Gertrude Lawrence and others, reactivated the American Theatre Wing, founded in 1917. They staged benefits for the war effort and founded the Stage Door Canteen, where stars worked as dishwashers and waiters and entertained the troops. The Wing coordinated seven Canteens across country and in London and Paris. Miss Perry then established funds to aid war veterans and in-need actors.

Miss Perry’s deft hand with comedy paid off co-producing and directing Mary Chase’s Harvey (1944), with Margaret working as costume supervisor. It won the Pulitzer over The Glass Menagerie, ran four years, and became a Hollywood hit.

Frueauff played the stock market with great success and guided his wife to shrewd investments. Unbeknown to most, Miss Perry was an inveterate gambler. “The seed money for many an American Theatre Wing activity or show investment came from her track winnings,” said her daughter. “Even during board meetings, mother played the horses. She’d have her secretary tiptoe in with the odds, then place a wager with a bookie.”

Miss Perry dreamed of a national actor’s school, a goal realized in 1946. Soon after, she developed heart problems. She refused to see a doctor. “The only thing that alleviated her pain was Brock’s nightly call,” stated Margaret.

In June, as Margaret and sister Elaine (later an actress and producer/director) planned a celebration for her 58th birthday, Miss Perry suffered a fatal heart attack. She was $300,000 in debt and living on $800 a week from Harvey royalties.

According to Margaret, “Mother was a fool for the theater. She lived and breathed it.”

Pemberton proposed an award for distinguished acting and technical achievement in theater. At the initial event, on April 6, 1947, at the Waldorf-Astoria, he handed out awards. Pemberton called them a Tony. The name stuck.

Ellis Nassour is an Ole Miss alum and noted arts journalist and author who recently donated an ever-growing exhibition of performing arts history to the University of Mississippi. He is the author of the best-selling Patsy Cline biography, Honky Tonk Angel, as well as the hit musical revue, Always, Patsy Cline.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…