1961 was a troubled and dangerous time for young black men in Jackson, Mississippi.

Despite KKK activity and White Citizens’ Council policing black and white known or suspected Civil Rights activists, two young African-American students made a pact for the Mississippi Civil Rights movement.

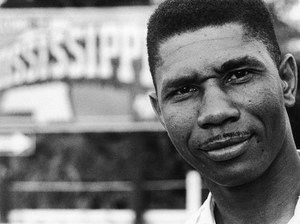

Irvin C. Walker, Jr. and Cleveland Donald promised Civil Rights leader Medgar Evers to step forward and break racial barriers at white colleges when they graduate from high school. Evers did not live to see the two Jackson students fulfill their promise. Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the White Citizens’ Council, assassinated Evers on June 12, 1963.

Walker, now retired after working in a family business and serving as an Urban League executive, remembers going with Cleveland Donald to meet regularly with Medgar Evers whose office was in the Masonic temple just around the corner from Walker’s school. Walker was the president of West Jackson Youth Council and Donald was president of North Jackson Youth Council of NAACP.

Ever’s death had a detrimental effect on the movement. Walker said, “We were in turmoil when he was killed. We had so many plans centered on him, (his death) was a big setback, but his death enchanced the movement. All of us looked up to him.”

“Cleveland and I made a pact and promised Medgar we would apply for admission and break the racial barrier at Ole Miss when we graduated from high school,” Walker said. “The NAACP retained Constance Baker Motley, the famed Civil Rights attorney and a member of its legal defense fund, to handle legal issues for all of us.”

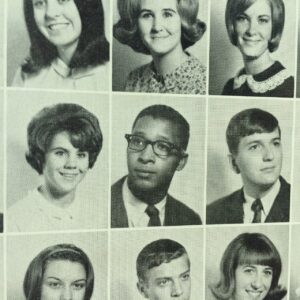

James Meredith became the first African-American to enroll in 1962, followed by Cleve McDowell, Cleveland Donald and Irvin Walker. The following year, Walker was joined by Joyce Jones, Ernest Watson and John Donald, Cleveland’s brother who is now a general session judge in Memphis.

James Meredith, Cleve McDowell and Cleveland Donald were admitted under court orders. But Walker became the first African-American to enroll at the University of Mississippi without a court order.

“Ms. Motley was prepared to do the legal work to get me admitted when I received a letter of admission from Ole Miss in late July of 1964,” Walker said. “I was shocked and scared somewhat. I was admitted just like any other student.”

Cleveland Donald enrolled first at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi and later transferred to the University of Mississippi where he and Walker became roommates in LaBouve Hall dormitory.

“I was treated just like everybody else even to the extent that a group of upperclassmen came to my room, took me to the courtyard in front of LaBouve and shaved my head just like all other freshmen,” Walker said.

Walker said Donald and he did not have too many problems at the University of Mississippi, but incidents happened regardless.

“We attended every event possible and at one ballgame, a fan didn’t like Cleveland’s and my applause for a black player on the opposing team,” Walker said. “He followed us back to the dorm, knocked on the door and said, ‘So this is where you n—–s live.’ I took him on and we rolled and tumbled down the stairs and I guess I got the best of him and he left.”

On one occasion in 1965, Walker recalled a scuffle with a fellow student who spat on him during a class changing period. Both students went before the judicial council that issued them appropriate disciplinary actions.

Walker said that despite catcalls of the n-word, he and Donald never used the buzzer that connected their room to the police station across the street.

As a liberal arts major, Walker finished school at the University of Mississippi and returned to community involvement with both the Chicago and Jackson Urban League affiliates. He left Mississippi in 2001 when the state failed to abolish the Confederate emblem from its state flag.

“There were boycotts by national groups, the convention business dropped off and I just saw the state in decline so we moved to Memphis,” Walker said.

Even now, Walker dresses for a game day in a red and blue shirt with an Ole Miss cap. He enjoys walking through the university campus and the Grove on a football weekend with his son, Irvin Walker III and his granddaughter, Jada Walker of Jackson. His granddaughter is now a junior at the University of Mississippi.

“Ole Miss gave me a great foundation and I am proud that my granddaughter is now attending the university,” Walker said.

Walker’s niece, Charmayne Walker Fillmore, also graduated fro the University of Mississippi with a bachelor’s in English in 1990. Both Walker’s son and his granddaughter are proud of his contributions to the Civil Rights movement.

“What my Dad and others did was really something,” Irvin Walker III said. “It was an awful time. I would not want to do what he did myself, but they knocked down some barriers for me.”

“I think it is really amazing what my grandfather did,” Jada Walker said. “I never really knew much about Ole Miss or racism. To know that he had his hands in this experience is kind of crazy. He was such a strong man. I am very proud of him.”

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram and Twitter @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…