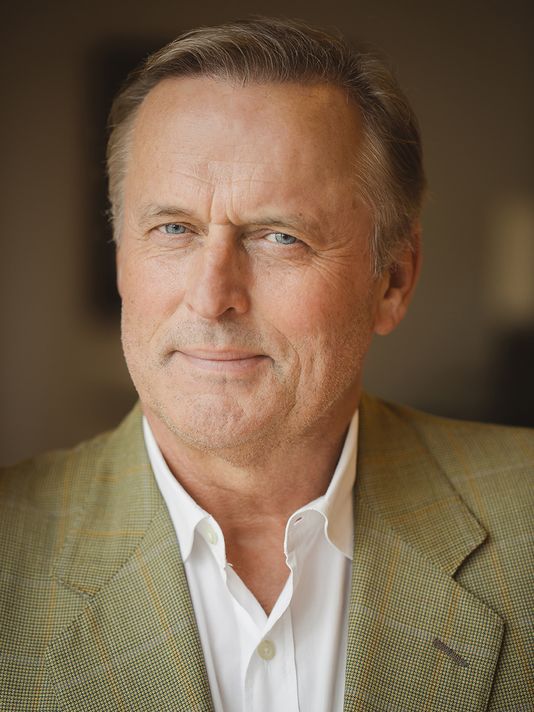

Grisham coming to Jackson: On August 22, John Grisham will speak at the first Mississippi Book Festival, to be held at the state Capitol. For more information, visit http://msbookfestival.com/ or call 601-906-8698. Below is Jerry Mitchell’s profile of the author from the July issue of MAGNOLIA Magazine.

He couldn’t hit a curve ball. He ditched accounting. He grew bored with the law. He grew even more bored with the Mississippi Legislature. Then he wrote a book.

America’s most popular writer of legal thrillers grew up on a farm a few miles from Black Oak, Ark., which seemed a thousand miles from anywhere else. John Grisham was the second of five children on this flood-cursed land, where his father struggled to grow cotton.

His father soon traded farming for construction, which sent the family packing to Louisiana and then to such places in Mississippi as Crenshaw and Ripley before settling in Southaven, which became their home in 1967, when John was 12.

Longtime teacher Frances McGuffey recalled their arrival. Grisham’s mother, Wanda, asked two questions: “How many books can you check out from the library?” and, “Where’s the Baptist church?”

McGuffey said Grisham’s mother “was tough on the kids and always had them in church.”

She recalled that Grisham’s father was “a great storyteller. Mr. Grisham was a wonderful guy, a deacon in the church.”

Southaven and Steinbeck

John Grisham attended Horn Lake High School in DeSoto County with his peers. Overcrowding was so terrible that students met in church classrooms and gathered in gyms with only a curtain separating classes.

In 1971, Southaven High School was constructed, and Grisham and other students from Southaven had a choice: Continue attending Horn Lake, or switch to Southaven.

Grisham chose Southaven, where he continued to play football, basketball and baseball.

When Horn Lake and Southaven first played in football, Southaven lost. McGuffey said after the game, some Horn Lake players taunted their former teammate, Grisham, who joked that maybe he should have stayed there.

In senior English, McGuffey taught students about King Arthur and decided to have the class read John Steinbeck’s “Tortilla Flat” as a parallel story of adventures.

While she was grading papers one day, Grisham slipped in to speak to her. “I really enjoyed ‘Tortilla Flat,’ ” he said.

McGuffey wondered if he was kidding. She took him for someone more interested in sports.

“Would you recommend another Steinbeck book?” he asked.

She said he should read ‘Of Mice and Men.’ ”

Time passed, and Grisham slipped in again to talk. “I really liked ‘Of Mice and Men.’ Do you have another one?”

This time, she recommended “The Grapes of Wrath.”

Grisham later told her he reread the novel every year. “I never dreamed it would inspire him to be great,” she said.

Mrs. Pickle

Grisham tried several blue-collar jobs before learning that pouring asphalt on a Mississippi highway with a rowdy crew could be dangerous.

That inspired him to attend Northwest Mississippi Community College, where he joined his childhood friend, Bubba Logan, and his roommate, Parker Pickle, who had both been attending for a year.

Grisham went home with Pickle, who grew up in nearby Love. His family lived on a dairy farm and had a field for a garden, Pickle said. “I’m one of eight kids, and my mother was the best cook that ever lived.”

She was a scratch cook, never writing down a recipe.

Instead of turkey and dressing, she served tomato dressing. “It was to die for,” Pickle said. “It was the best stuff I’ve eaten in my life.”

Pickle made an offer to his two roommates that he would learn to cook if they would learn to clean.

“Parker’s cooking showed potential,” Grisham recalled, “but then we would eat anything. I do not remember cleaning any apartment or dorm room during my seven years of college. I know for a fact that Bubba didn’t either.”

Logan said Pickle cooked plenty when he and Grisham decided to fast for the week. “He made homemade biscuits. All we had was a six-pack of water.”

Pickle described Grisham as “very reserved” to those who didn’t know him, but in private, “he’s got a wicked sense of humor. He’d hang out with me because I’m one funny son of a b—-.”

Grisham recalled, “Bubba has the quickest tongue, Parker the wickedest sense of humor. I could never keep up with them.”

He thought he would shine as a star in baseball when he arrived at Northwest. Instead, his grades suffered (he failed freshman English), and he wound up riding the bench.

“I decided I needed to leave,” Grisham joked. “I could not trust such a promising career to coaches with such limited vision.”

Eventually, the trio — “Bubba was no doubt the ringleader,” Grisham said — decided to go to Delta State University. “Baseball was a factor, but the overriding attraction was the rumor that there were large numbers of pretty coeds with questionable morals. Such rumors have always fascinated Bubba and Parker.”

The curve ball

In fall 1974, the trio arrived at Delta State in Cleveland, and it didn’t take them long to find Ma Redmond’s Boarding House. “It was all you could eat for $1.25,” Pickle recalled. “For college kids, it was a godsend.”

Grisham tried out for the baseball team at Delta State. He believed legendary coach Boo Ferris would recognize his talent.

One day, he stepped up to the plate to face pitcher Stewart Cliburn, who had been drafted by the majors.

When the pitch headed straight at his head, Grisham hit the dirt. He heard “strike” and the laughter of his teammates as the curve ball crossed the plate.

Ferris spoke with him later, a conversation he recounted in Rick Cleveland’s biography on the legendary coach, “Boo: A Life in Baseball, Well Lived”:

“John, you had trouble with that curve ball yesterday,” Ferris said.

“Yes sir, I thought it was going to hit me.”

“That’s why they throw them like that.”

“I guess so.”

“And you had trouble with the fastballs last week.”

“Yes sir. They’re awfully fast.”

“Well, if you can’t hit a fastball and you can’t hit a curve, what can you hit?”

“A change-up, if I know it’s coming.”

“I see. Look, I was once a pitcher, and pitchers can be cruel when they spot weaknesses.”

“I’ve never liked pitchers.”

“Well, they show up at every game.”

“I despise them.”

“Your grades are not too impressive.”

“Yes sir, I’m sort of drifting right now.”

“I suggest you forget about baseball and hit the books.”

“I think you’re right.”

Another university, another major

A semester later, the trio made their way Mississippi State University. “The rumors about the women didn’t pan out,” Grisham said. “Most importantly, Bubba grew a beard and decided he wanted to study forestry.”

Grisham found a home at State, “but then there were more rumors about loose women at Ole Miss, so off they went,” he joked. “They eventually got degrees from Ole Miss.”

When Grisham showed up unannounced at the admissions office at State, he had no transcript and no paperwork. The office kindly took his check, only to see it bounce.

His future seemed less clear. He had changed his major three times in three semesters and decided he would take a shot at finance.

It only took him a few classes to figure out finance held no future for him, either.

Inspired by a talk with a Vietnam veteran who was majoring in accounting and planning to be a lawyer, he decided to follow suit and dedicated himself to his studies.

He traded his dream of baseball for a dream of becoming a tax lawyer making millions representing the rich, maybe even baseball players.

Each morning, he read The Wall Street Journal in hopes of preparing himself for that world.

In a business correspondence class, a professor sent Grisham a note saying how easy his writing was to read. It was the first time anyone had complimented his writing.

Although some former classmates said Grisham caught “novel fever” before graduating from Mississippi State in 1977, he joked, “I don’t remember contracting novel fever in college. I contracted a few other things which should not be repeated.”

A life in law

In 1981, Grisham graduated from the University of Mississippi School of Law. He returned to Southaven, married and practiced law with Larry Vaughn.

They opened their office on Stateline Road. “We liked it because it was all glass in front,” Vaughn said. “We thought it was the neatest thing at the time.”

Grisham recommended one change. Rather than having clients sit across desks, “we’re going to have a round conference table, where we can all sit equal,” he said.

Whatever client came in the door, that was the law they practiced. Much of that was family law.

While Grisham saw the big picture, Vaughn repeated to Grisham they needed to get serious about their bread-and-butter cases that were paying the bills.

At one point, Grisham balked at handling any more divorce cases. “I’d rather starve,” he said.

The declaration surprised Vaughn, who knew the cases were bringing in good money.

“John Grisham was in an environment that didn’t promote his vision,” Vaughn said. “He had to swim upstream. I have to give him credit.”

He said Grisham believed handling such cases kept them from seeing the possibility of big ones.

Finally, a few cases they’d dreamed of began to come their way. They represented clients in train collisions, auto crashes, and product liability cases.

“We became tort gurus and the things he’s written [about] in books,” Vaughn said.

They also saw criminal cases.

In the DeSoto County Courthouse, Grisham handled his first murder case. He became so nervous he had to go to bathroom before delivering his closing statement.

When he did speak, he apologized to the jury for being such a novice. He won anyway.

The Legislature

In 1983, Grisham ran for the state Legislature and won. He began serving in January 1984 and earned an $8,000 salary, which was more than he had brought in during his whole first year as a lawyer.

By March, “I was sick of it,” he recalled. “I would have had to serve 20 years before I got any kind of real responsibility chairing a committee. I just felt like it was an enormous waste of time.”

He joined fellow freshman lawmaker Bobby Moak for lunch at places such as Dennery’s, and at night they might hit George Street Grocery, Hal & Mal’s or Willie Morris’ home, where they would often greet the dawn.

“John’s an old soul who makes quick decisions,” Moak said. “For the most part, they’re the right ones.”

‘A Time to Kill’

In the summer of 1984, two teenage girls were raped, brutalized and left for dead in a farmhouse not many miles from Grisham’s law office in Southaven.

“It was one of those crimes you never forget,” Grisham recalled. “I was praying I would not get appointed to represent the defendant.”

He wound up hearing the confession on tape, the rapist sharing details of the crime with all the emotion of reading a shopping list. “It was pretty coldblooded,” he said.

That fall, Grisham watched as the girl, who had just turned 13, testified about the horrors of that day. The longer he listened, the angrier he grew.

When the break came, he dashed down the stairs, only to realize he had forgotten his briefcase. He returned to the courtroom and came eye to eye with the rapist.

The thought overwhelmed him that if this had been his daughter and he had a gun, he would have gotten his revenge on the spot.

The jury convicted the rapist and sentenced him to life without parole.

On Grisham’s three-hour treks between the state Capitol and Southaven, an idea began to form in his mind. Moak recalled Grisham asking him, “What if you had a daughter that was raped? What would you do?”

“If I could get my hands on him,” Moak replied, “I’d kill him.”

When Grisham returned home, he began jotting down ideas in his steno pad. On the inside cover, he played around with titles. He finally settled on “A Time to Kill.”

Stealing time

Any moment he could steal, Grisham wrote.

He got up early each morning and wrote as much as he could between 5:30 and 7:30 at his law office.

At the DeSoto County Courthouse, he sneaked upstairs to the law library and scribbled for a half hour or more. At night, he wrote on the family’s dining room table.

At the state Capitol, when debates grew boring, he quit taking notes and returned to writing his book in the notepad he hauled with him wherever he went, “everywhere I could steal 10 minutes,” he said.

Moak recalled Grisham dragging him from their condo to the bookstore in nearby Northpark Mall. “He would go in and buy five or six books,” he said. “I’d tell him, ‘Man, you are reading a lot.'”

Grisham would buy historical books, well-known novelists, Moak said. “He was in his room a good bit, reading and writing. I think he figured out their formula, and then I think he figured out his formula.”

It took Grisham three years to write “A Time to Kill” and another year for his agent to sell it.

The only taker the agent could find was Wynwood Press, a little-known imprint of Fleming H. Revell Publishing, known for its Christian publications. The $15,000 Grisham received enabled him to pay off the family’s credit cards.

His editor was Bill Thompson — the same editor who had discovered Stephen King.

Killing time

Grisham drove with his friend, Bill Ballard, to Oxford. The two were so close that Ballard had read chapters of “A Time to Kill” before it was published. Ballard’s wife, Brenda, had taught Grisham English in the eighth grade.

Inside Square Books, the two men visited with owner Richard Howorth. Grisham said 5,000 copies of “A Time to Kill” were being published and that he would like Square Books to sell 500 of them.

Howorth responded that it was difficult for his store to sell that many copies for a known author, much less an unknown one. He explained that in order to increase sales, he would need to develop some enthusiasm for his book.

The next thing he knew, Howorth was the one having to read the book. “He came back with a manuscript copy,” he recalled. “I was mad at myself for volunteering.”

That night, Howorth kept his word and began reading the novel. “At 2 a.m.,” he said, “I was still going.”

Pete Dexter’s “Paris Trout” had just won the National Book Award, and Howorth concluded that “A Time to Kill” was even better.

Grisham printed invitation cards, which Howorth mailed out, inviting people to the book signing for this “fabulous first novel.”

When Grisham and his wife, Renee, drove into Oxford, they circled the courthouse square, peeking inside the windows of Square Books. They saw no one.

The couple eventually parked and went in. “I was almost afraid to enter such an empty bookstore and was so relieved to find a nice crowd upstairs,” Grisham recalled. “Richard was great. We sold about 50 books that day. As I learned, that’s a successful signing.”

Selling time

Grisham used his author’s discount to buy 1,000 of the 5,000 copies of “A Time to Kill” and soon learned that selling books was a lot tougher than writing them.

He sold the $18.95 book out of his trunk and begged friends to buy it. In his law office, he sold them to clients for discounted prices of $10 or five dollars. He even used one as a doorstop.

During these struggles, he questioned his agent about sales. One day, his agent angrily told him to go write another book.

He did.

That book turned out to be “The Firm.” When his agent read his two-paragraph summary, “he went nuts,” Grisham recalled. “He kept saying, ‘This is a big book.’ ”

Grisham took a step of faith to enter the writing business full time. He quit his law practice and the Legislature and literally bought a farm, this one with an A-frame house in Oxford, where he hoped to write and raise kids.

When Moak found out, he rang Grisham up. “You freaking idiot,” he said. “What the hell are you doing?”

A number of months later, Moak spoke again with Grisham. “He is literally down to the point of saying, ‘Next week, I’m going to have to get a job.’ ”

Not long after that conversation, Grisham got a call from his agent that the movie rights for “The Firm” had just sold for $600,000.

He telephoned Moak, who shot back with a laugh, “Where’s my cut?”

Square Books became a frequent hangout for Grisham, who drank the store’s cappuccino and signed copies of “The Firm.”

On the morning of March 13, 1991, he was inside the store when news came that “The Firm” had landed on The New York Times Bestseller List, a place it would remain for almost a year.

“I remember him picking up the phone by the café counter and taking the call,” Howorth said. “You could tell the minute he picked up the phone it was good news.”

Back to the courtroom

“The Firm” sold 7 million copies, and “A Time to Kill” was reprinted. This time, Grisham didn’t have to sell the book out of his trunk.

Over a dinner of fried catfish and crawfish tails with Moak in 1992, Grisham jotted down on a legal pad the possible titles of a dozen future books, several of which he wound up writing, including “The Rainmaker,” “The Partner” and “The Associate.”

In 1996, Grisham returned to the courtroom to keep a promise he’d made to the family of a railroad brakeman, who was killed when he was pinned between two cars.

“Are you as nervous as I am?” he asked potential jurors crowded into the 76- seat courtroom in Brookhaven. “It’s been seven years since I tried a case. I’ve got the jitters. If you’re a little bit jittery, too, that’s OK.”

He tried the case with Moak and veteran trial lawyer Danny Cupit.

A young judge named Keith Starrett heard the case. He remembered Grisham as a “genuinely nice guy. He didn’t act like he was a celebrity.”

He also remembered that Grisham “can tell a pretty good story. That’s a lot of what you do when you present a case to a jury. He has a real knack for presenting things to the jury.”

After two hours of deliberations, the jury awarded the family $683,500 — the biggest verdict of Grisham’s legal career.

‘So many stories to tell’

Grisham has now sold more than 300 million books. His estimated net worth has topped $200 million.

The good news is Grisham “hasn’t changed any,” Moak said. “He’s a doting father, and he’s raised his kids right.”

His daughter, Shea, is now an elementary teacher, and his son, Ty, is practicing law.

When Hurricane Katrina ravaged Mississippi in 2005, Grisham flew down to witness the destruction for himself. He and his wife started the Rebuild the Coast Fund, which gave $8.8 million in direct aid to devastated families.

Grisham said he still writes “because I have so many stories to tell, so many bad guys to go after, so many injustices to address. It’s still great fun.”

He confessed, “I’m not sure what I would do with my time if I didn’t write a few hours each day.”

Each year, when his new novel hits the shelves, signed copies arrive at the homes of his high-school English teacher Frances McGuffey, his college roommates, his one-time law partner Larry Vaughn, and his friends Bill Ballard and Bobby Moak.

McGuffey displays them in her Southaven home. She speaks fondly of her former student. “He is dearly loved,” she said. “He’s so good about remembering his roots.”

John Grisham’s Mississippi

Memphis ends at the Mississippi line, which is where Southaven begins. The once slumbering suburb is now one of the fastest growing cities in the U.S. Grisham attended both Southaven Elementary School (8274 Claiborne Dr.) and Southaven High School (735 Rasco Rd. W.), where his books are on display.

John Grisham’s one-time law office (40 Stateline Rd. W., Southaven) still exists. It is the State Farm office of Barry Bouchillon, who rented space to Grisham.

Grisham sometimes slipped off to nearby Robinsonville to eat at the “deep-fried paradise” known as Hollywood Café (1585 Old Commerce Rd.). He mentioned the iconic place in “A Time to Kill.”

Thirteen miles south of Southaven is the DeSoto County Courthouse (2535 U.S. 51, Hernando). In the courtroom, Grisham heard a young girl’s testimony that inspired him to write “A Time to Kill.”

More than 100 miles south of Hernando is Dave “Boo” Ferris Field at Delta State University (1003 W. Sunflower R.d, Cleveland), where Grisham unsuccessfully tried out for Ferris’ baseball team.

Two hours west of Delta State is Mississippi State University (75 B.S. Hood Dr., Mississippi State), where Grisham graduated with an accounting degree in 1977. On the third floor of the Mitchell Memorial Library is the John Grisham Room, which features an original handwritten copy of “A Time to Kill” and other manuscripts and memorabilia from his career.

Nearly two hours to the north is the University of Mississippi School of Law (481 Chucky Mullins Dr., University), where Grisham graduated in 1981. Students now do research at the John Grisham Law Library.

NearbySquare Books(160 Courthouse Square, Oxford) is where Grisham held his first bookstore book signing and also where he learned “The Firm” had hit The New York Times bestseller list.

Two and a half hours south is the state Capitol(400 High St., Jackson), where Grisham served from 1983 to 1990. Not far away is where he held his first book signing in Jackson,Hal and Mal’s(200 Commerce St.), a pub that also appears in his books.

Lemuria Books (Banner Hall, 4465 North I-55, Jackson), which helped promote “The Firm,” is another Grisham favorite, and he continues to sign his novels for the store.

In 1996, Grisham returned to the courtroom and won a case for the family of a railroad brakeman, who was killed when he was pinned between two cars. The trial took place at theLincoln County Courthouse(301 S. First St., Brookhaven).

When Grisham makes his way back to the Mississippi Gulf Coast, one of his favorite places to eat is Mary Mahoney’s Old French House(110 Rue Magnolia, Biloxi), which appears in his novel, “The Runaway Jury.” When Katrina hit the Gulf Coast in 2005, Grisham returned to Mississippi to check on the family that runs the restaurant and others who were devastated by the hurricane.

Posted with permission from The Clarion-Ledger