My friendship with the Cofield family stretches back more than 50 years. Col. J. R. Cofield was an early and valued mentor and his son Jack was a co-worker at the University of Mississippi. The Col. and Jack were well-regarded photographic artists and had a great knowledge of and appreciation for Oxford, its roots and its history. John Cofield, Jack’s son, inherited the keen sense of history, appreciation of culture, and the art of writing a story, for which both Col. Cofield and Jack were well-known. John is a valued contributor to HottyToddy.com and through his work here and on his blog, he is known and loved by thousands who also love Oxford and Ole Miss. — Ed Meek

John Faulkner, “Grand John” to kin, was the first to know. To know that somehow, someway, things would never be quite the same. And not simply the obvious, as he sat staring at Oxford’s courthouse lawn, waiting in the wee hours for them to bring his dead brother, Bill.

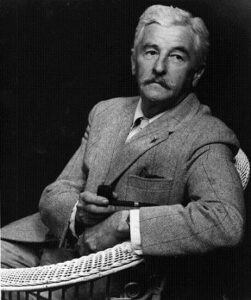

Photo by Jack Cofield (c) The Cofield Collection, Archives University of Mississippi Libraries

Three months or so ago, William Faulkner had been sitting a couple of blocks away, posing at Cofield’s Studio. Old friend, J. R. “Colonel” Cofield, had always been behind the lens, but now son Jack worked the shutter for the first time, and Mr. Faulkner’s last. Distinguished, a refined British air; tweed jacket, silk tie, silver-haired, now a Man of Letters. Now, he was gone. It was early July ’62.

Oxford knows more than Jefferson. Knows generations of leaders and town fathers, all so uniquely Southern, the characters down through the decades, the Falkners of Mississippi. Now, brothers John and Jack, nephews Jimmy and Chooky, stood watch at Rowan Oak, over the parlor where he lay. Any petty past be damned, that morning’s hushed respect remained and swiftly brought the town to understand a loyal defense of this fine old Southern family, as the Faulkners of Oxford issued the following:

“Until he is buried he belongs to the family. After that he belongs to the world.”

Our finest hour tolled some 4,700 miles from Lafayette County, Mississippi, as King Gustaf Adolf of Sweden, presented the 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature to William Cuthbert Faulkner. But in the last blink of Jefferson’s eye, Stockholm would now come to Oxford. And more than Grand John knew, or we could have imagined, here they would come.

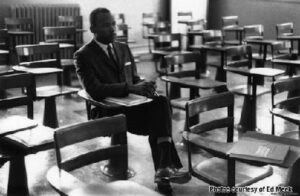

Photo by Ed Meek (c) 1962 Meek School of Journalism and New Media – University of Mississippi Libraries

Riding, walking and stumbling in drunk, Oxford has intoxicated many a pilgrim poet in search of Mr. Bill’s Yoknapatawpha vibe. But it is not as elusive or romantic as all that. It stands strong in stone at the heart of our two worlds, where both built it. Where now Grand John’s mournful gaze upon its lawn could not have foreseen the second pall to soon fall on brother Bill’s courthouse square.

Colonel Cofield, as with the closest, mourned no wordsmith, no Laureate. Rather for a gentleman’s bond now absent by half, but made no lesser from six feet away. That sweltering summer of our sadness drug on as the world wrote its golden reviews of our man. But black type on white background ran into Confederate gray and the shroud from which we had to emerge darkened still and we braced for impact as James Meredith, a negro, telegraphed the following:

“I plan to enroll in Sept. Please advise when to report for registration.”

Now we knew, to a man we knew, there would be trouble. No clear path through or way around it. Shiloh’s 1862 stains in the halls of the Lyceum had never dried and Governor Barnett’s blood letting reopened our wounded history books to include the last clash of the Civil War, the Battle of Ole Miss. All that could be penned had been. It was late September ’62.

James Meredith is a Rebel’s Rebel. A right Rebel. Even the old hard haters of his guts, respected his guts. He was going to attend the University of Mississippi and love Ole Miss, with equal rights and passion, with or without us. Defying the Governor’s demands, forcing the Kennedy’s hand, he marched on, soldiered on, as he does this very hour, immortalized at our very core, forever in bronze on the grounds of the Lyceum.

Photo by Ed Meek (c) 1962 Meek School of Journalism and New Media – University of Mississippi Libraries

Dignity and a quiet resolve live there. The life and times of University of Mississippi alumnus, James Meredith, speaks to the heart there. Minds change, and change, and change again still. But enlightened hearts of Ole Miss freshman shine the way to our bright shared future. And set in stone there, “Courage, Knowledge, Opportunity, and Perseverance,” speaks to the world as to what one right Rebel can do.

The battle was joined in front of the Lyceum a little after 8 that Sunday night, as 400 Federals fired tear gas into the approaching Rebels. Bullets were returned. On the lawn of the pretty English Tutor, across from campus and on University Avenue from beautiful Memory House’s front porch, both J. R. Cofield and John Faulkner understood clearly the ugly shots heard round our world. Orange glows lit the sky while the sad gas and news drifted outward, but any tears shed were inward. Oxford’s sons had been here before.

Photo courtesy Ole Miss Athletics

Jack Cofield, in the first years of a noted photography career at Ole Miss, rode out the night in and around the fighting at the Lyceum. Chooky Falkner, in the early years of a military career that would retire him as General Falkner, was treated for his injuries that night. Armed with the Declaration of Independence, applicant James Howard Meredith remained under armed guard as the fighting went into the small hours. Across campus, John Howard Vaught held a football team in check. There would be blood and blame enough to go around, but neither on his Ole Miss Rebels. He was undefeated and by sunrise, the only Rebel left so.

Before the pilgrimage to Jefferson could be literary, the march into Lafayette County would be military. A century’s bookend to 1862, found US troops once again crossing the Tallahatchie, south for Oxford. Thirty-one thousand strong came to call, this time. Campus and county found Faulkner’s surrounded Courthouse surrendered as bayonet-fixed 101st Airborne Screaming Eagles patrolled the halls of the Lyceum. A little after 8 that Monday morning, University of Mississippi Register, Robert Ellis, enrolled fellow Mississippian, James Meredith, a black man, at Ole Miss. It was early October ’62.

Photo by Walt Mixon

The earthquake cracks, but the aftershocks crumble. The hurricane’s eye gives way to the ambushing backside. And so it was, as the bodies of local Ray Gunter and reporter Paul Guihard were shipped back to their mothers in Yocona, Mississippi, and London, England, respectively, in shipped the world press, disrespectfully. Formally the Chancellor’s boardroom turned international press hub, now served hundreds of newsmen with little space for their craft or southern sympathies. The Fall of our fall brought a surely righteous changing of color as the world wrote its dark reviews of our land.

The Faulkners and Cofields, as with the closest, mourned no loss of pride; for the hard Oxford road traveled had built more than it could ever take. Still, but barely standing, we had been laid low by our 100 years and 15 minutes of fame, and infamy. So, with William, “Brother Will” to kin, buried, Oxford occupied, James Meredith now a right and righteous Rebel, two more graves dug and covered and troops camped on the practice field, the critical eyes of the world upon us, we rose in the only way we had left.

Flying, riding or marching mad into our Fall had come generals and privates, right and wrong writers, mourners for Jefferson’s past and mourners for Oxford’s future. Little noticed among the herding ink slingers was a small crew from around the state. Mainly Mississippi boys at first, but not an agitator in the bunch. Pen in hand, they too were searching for something in Oxford. Not trouble, but tribute. They weren’t looking for Johnny Reb…they were looking for Johnny Vaught.

The ’62 campaign began with the fall of Memphis, then the Wildcats from Lexington went down in Jackson. But a strange thing happened on the way to the Sugar Bowl. At Kentucky’s halftime, politics tackled football at the 50 yard line and the result of the Governor’s play left the next game a Rebel Homecoming without a home. The program cover reads Hemingway Stadium, but American presidents defer to no Queens. The season still granted though, Vaught and his Rebels went on the road, and on a tear. Down went Houston, Tulane and Vandy by a combined 96-7.

Photo courtesy UM Communications

Coach Vaught, as with the closest, mourned no loss of Hemingway, for the road less, and more, traveled was a long quiet friend. And so it was that Johnny’s Rebs, now 5-0, rolled into Baton Rouge. Once upon a war and a far away battlefield, the University Greys and Louisiana Fighting Tigers had charged, fought and died side-by-side. Now ally turned enemy, and ten decades removed to a Southern field, Vaught’s Glynn Griffing led Rebels charged into the battle at Death Valley. It was early November ’62.

He had been forced to the road as a coach with the big hopes of little Oxford, Mississippi, riding with him. And after a grudge match that would typify what Ole Miss vs. LSU will forever mean to the twin Magnolia states, the scoreboard read Rebels 15…Tigers 7. When the boys rolled back into town, John Howard Vaught returned at their helm as an Ole Miss legend. Because now we knew, to a man we knew, that while folklore warns they come in 3’s, old wives tell tales of the charmed triplet. He took the town’s helm and over his 25 years as the Father of Ole Miss football and the decades as University of Mississippi elder statesman, these were his finest Oxford hours.

Chattanooga never stood a chance, now we were 7-0. It wasn’t a game anymore. Oxford had been mourned, Ole Miss scorned, but with Coach leading the way, both reborn. Neither Tennessee nor Mississippi State could muster 7 and when the final horn of the final game of the final season of the old days and ways sounded at Hemingway Stadium, we knew that somehow, someway, things would never be quite the same. And not simply the obvious as we stood cheering the Champions of the Southeastern Conference on a football field surrounded by our ashes. It was early December ’62.

Christmas came to Oxford that winter of our winning Rebels with equal parts pride, hope and our own hushed sympathy. And that never ending American spirit of renewal grew stronger still as year’s end found Johnny and his Rebels once again crossing the Mississippi, south for New Orleans. For many, a sense of destiny had already told that this time, the exclamation point on our season of sunsets and sunrises, would not be in defeat. The Sugar Bowl, as always, was sweet for Vaught. The Universities of Arkansas and Mississippi clashed in a southern brawl that would find Oxford’s morning after hearts bursting with an undefeated spirit and a new beginning. It was early January ’63.

Photo courtesy Rusty Faulkner

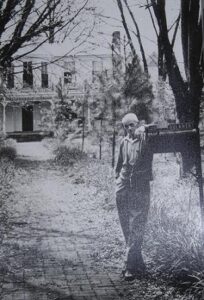

Where have you gone old Oxford town? Colonel Cofield’s photography and world had been black & white, son Jack’s had both progressed, rightfully so, to color. Together they left the pictorial history of friend Faulkner in his element. Grand John’s eldest son, the one Brother Will never had, Jimmy, had once returned home to Oxford on Christmas Eve, 1945, a war hero. And it was Jimmy who brought William home to John in those smallest of hours. Jimmy raised another generation of Oxford Faulkners and then went on to find his own pen. He died on Christmas Eve, 2001. Johnny Vaught won a total six SEC championships, but none bigger than ’62. He lives forever in our collective Oxford hearts as the honored Patriarch. And in his last years at the helm, he left his living legacy when under his wing he took a fatherless brokenhearted kid who went on to become the father of the First Family of Football. He is ours and we are his, and forever kids in Archie’s Army. Coach Vaught lived a long full retirement in full support of Ole Miss and passed away peacefully in Oxford at age 96. After forty-three years, Colonel Cofield closed his photography studio in 1971, and spent his last years actively devoted to his old friend Bill. He died in his sleep in Oxford in 1980. The younger Cofield authored the family’s William Faulkner collection. Then he too spent his retirement devoted to his famous subject, and passed away at home in Oxford in 1990. Grand John Faulkner had been the first to know. To know that Jefferson would never change again, but Oxford would never be the same. Nine months later he and his typewriter, too, fell silent. So, now they are all gone, all resting at St. Peter’s, all…save one.

Back in ’82, Jack Cofield, camera in hand, crossed the stage at Fulton Chapel and shook hands with his friend and long time subject, James Meredith. It had been twenty years and taken most of them for the smoke to clear. But while the semesters slipped further into the future, that day’s respect remained and slowly brought the old guard to understand a loyalty to this Rebel’s rebel, our right Rebel. His likeness will never cease marching on at the Lyceum, while the Civil Rights icon himself can be seen walking the campus today. Once ringed by armed guards, as his appearance drew angry mobs, his homecomings now find him circled with awed adoring admirers. But dignity and a quiet resolve still surround the man who now strolls the Grove on game day as James Meredith, an Ole Miss living legend.

Oxford knows more than Jefferson. Knows the decades passed and with them went a small town. Time took her, but not the memories of a slower time. Nor can time take the memories of John, James and William, and what they did here. Once upon our lore, they wrote the history and future of Lafayette County, Mississippi.

Now-a-days critical ink can still flow around town, but we are true battle tested stewards now-a-days, too. America’s ire turned envy for our charmed southern Square has been wrought from a pride of citizenship that could only have come from our long march to here. William Faulkner, in death, marked both Jefferson’s and Oxford’s closing of a long held and well-remembered era. Until he was buried, both had belonged to us, after that he and we, too, belonged to the world, after those six months in ’62.

Many thanks to old family friend Jamie Henderson for her help with all the commas. And for gladly answering a constant flow of emails. To my brother Glenn, always my source for writing ideas, love ya brother. — John

John Cofield is a HottyToddy.com writer and one of Oxford’s leading folk historians. He is the son of renowned university photographer Jack Cofield. His grandfather, J. R “Colonel” Cofield, was William Faulkner’s personal photographer and for decades was The Ole Miss yearbook photographer. Cofield attended Ole Miss as well. Contact John at johnbcofield@gmail.com.

John Cofield is a HottyToddy.com writer and one of Oxford’s leading folk historians. He is the son of renowned university photographer Jack Cofield. His grandfather, J. R “Colonel” Cofield, was William Faulkner’s personal photographer and for decades was The Ole Miss yearbook photographer. Cofield attended Ole Miss as well. Contact John at johnbcofield@gmail.com.