We are burying Tom Freeland today. His death resulted from complications from major surgery, and like most of his friends and family, I am hard-pressed to understand and cope with his loss.

In thinking back over happy times spent with Freeland, I see that some of the best were in the Delta, for he was an authority on the Mississippi blues and a lifelong student of civil rights. For years I’d heard about his Delta tour given during the Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference. This eight-hour bus tour, in which he played the music of bluesmen over the sound system as the bus passed through their home towns and hamlets — Mississippi John Hurt of Avalon, Sonny Boy Williams of Tutwiler, Muddy Waters of Clarksdale — took me into a world I’d always known existed but never fully appreciated.

This is where civil rights met the blues. This is the Mississippi everyone should be allowed to experience, but only with a uniquely qualified historian and interpreter sitting in the front of the bus, fielding every question with enthusiasm and high spirits. Freeland was a tireless advocate for minorities and diversity and, like the great bluesmen, was mainlined into the harmonies and dissonances that are the Mississippi Delta.

On a day when we say farewell to Tom Freeland, friend and kinsman, HottyToddy.com has kindly agreed to reprise this story. Please join me on a tour of the Delta with a guide who was one of a kind.

— Larry Wells

We’re five miles west of Avalon, Miss., traveling an unpaved road in a chartered bus, when we arrive at our intended destination: the isolated community of Money, site of one of the most monstrous hate crimes in American history.

The bus stops at an abandoned building which was once the Bryant Grocery. The roof is falling in, the store front overgrown with vines. Our tour group, under the direction of attorney and blues historian Tom Freeland, and sponsored by the University of Mississippi, quietly emerges from the bus. No historical markers exist to show that this is where Emmett Till, 14, was murdered in 1955 for whistling at a white woman, the wife of store owner Roy Bryant. No signs tell us that Till’s disfigured corpse was found floating in the nearby Tallahatchie River, weighted down by a 70-pound cotton gin fan.

In the silence each of us focuses inwardly on the past. A palpable feeling of foreboding and menace hangs over the ruined country store. After an all-white jury found Till’s killers, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, not guilty, they confessed to the crimeknowing they were protected by double jeopardy. Emmett Till’s death galvanized support for the American civil rights movement, which took root in the town of Ruleville, just twelve miles from here.

“I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

(Fannie Lou Hamer)

Until I participated in this tour, I didn’t realize how close Ruleville is, geographically and spiritually, to where Till was murdered. It’s humbling to realize I’ve lived in Mississippi over thirty years without having made this connection. Ruleville is the hometown of civil rights legend, Fannie Lou Hamer. Less than ten years after Till’s murder, Hamer joined the 1964 Freedom Summer Project to help people register to vote and let their voices be heard.

Despite attempts to stop them from organizing meetings, Hamer and civil rights leader Robert P. Moses succeeded in forming the Freedom Democratic Party and eventually gained two seats at the National Democratic Convention. Hamer ran for Congress in 1964 and 1965 and was instrumental in implementing the “Head Start” program. Her theme song was “This Little Light of Mine.” The tour group gathers at Hamer’s grave bearing her famous motto: “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

“Get on board, little children,

Let’s fight for human rights!”

(from “The Gospel Train,” Jubilee Singers, 1873)

A yellow crop-duster plane circles overhead as we pass through the town of Drew, home to “Pops” Staples and his gospel singers (also the hometown of quarterback Archie Manning). The Staples Family became an influential gospel group in the civil rights movement with “message songs” such as Respect Yourself. They changed gospel lyrics such as “Woke up this morning with Jesus on my mind” to “Woke up this morning with freedom on my mind.” Other Staples favorites included Get on Board (1964), and Freedom Highway (1965).

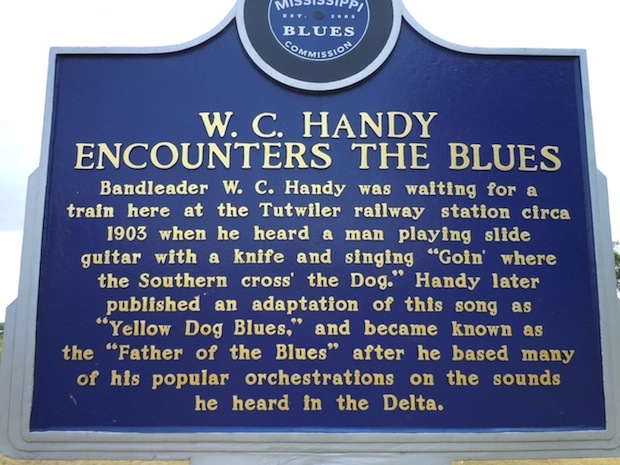

The hamlet of Tutwiler, fifteen miles to the north, claims to be the birthplace of the blues. A mural painted on a wall tells the story: In 1903, W.C. Handy, a band leader and cornet player in minstrel shows, was waiting to catch the train to Memphis. In the little station he heard a “knife on a guitar” (slide guitar). He went inside and heard a man singing, “Where the Southern cross the Yellow Dog,” a song about the dangerous, ninety-degree railroad crossing of the Southern and Yazoo & Mississippi Valley railroads.

Though Handy didn’t take to the blues right away, calling it “the weirdest music I ever heard,” he soon discovered its potential. He started a music publishing company and was the first to publish blues and ragtime. All that remains of the Tutwiler station platform today is a concrete slab with a historical marker, but the tracks still stretch north to Memphis, still lonesome, still singing the blues for those who care to listen.

Just north of Tutwiler, a curving gravel lane takes us to the site where harmonica legend Aleck “Rice” Miller, better known as Sonny Boy Williamson, is buried. Emerging from the bus with the tour group I find myself immersed in the rich smell of the earth, the thrumming sounds of insects and birds. Trees have sprung up in this country cemetery, giving some respite from the relentless heat. Previous visitors have scattered coins and guitar picks, whiskey bottles, and a few smooth stones around Williamson’s grave. Freeland observes that after Sonny Boy played with Eric Clapton and the Yardbirds he remarked, “These English boys want to play the blues so bad and they play the blues so bad.”

I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees,

Asked the Lord above “Have mercy, now,

Save poor Bob if you please.”

(“Crossroads,” by Robert Johnson)

I’ve always heard that somewhere in the Delta there is a crossroads where Robert Johnson (“Crossroads Blues”) sold his soul to the devil. “It’s just up the road,” says Freeland, tongue in cheek. At the juncture of Highway 49 and 61, a wrought-iron guitar sculpture prominently advertises this site as the devil’s crossroads, despite the fact that these two highways did not intersect here in Johnson’s day. Freeland explains that Johnson’s crossroads actually was more myth than reality, that to blues singers every intersection represented a choice between good and evil: one could “go straight” or “sell his soul” for fame and fortune. Still, he adds with a grin, if a guitar player waits at a crossroads at midnight, Satan may come and tune his guitar for him.

Our final stop is the Delta Blues Museum, housed in Clarksdale’s old railroad depot where in 1943 Muddy Waters (McKinley Morganfield) caught the train to Chicago. Among his disciples were the Rolling Stones, who took their name from one of his songs. The museum features a Muddy Waters cabin exhibit along with the original barber chair used by the “Barbershop Bluesman,” Wade Walton; guitars belonging to Son Thomas and Big Joe Williams; the piano, shoes and harmonica of Charlie Musselwhite; and the “Three Forks” sign from a juke joint where Robert Johnson was allegedly poisoned at his last gig.

A popular live exhibit is the Johnny Billington Blues Academy, a rehearsal hall where local teens play the blues during summer vacation or after school. The best of them have joined or formed groups like Super Chikan, Deep Cuts, and Blues Prodigy. These future R & B artists are serious about music and make it sound easy. I could listen to them all day.

As our bus crosses Highway 61 and heads east, we leave the Delta with a newfound appreciation for its tragedies and triumphs, its music and legends. At some point during Tom Freeland’s blues and civil rights tour, each of us came to a crossroads and made a personal choice, letting the Delta become part of us. We couldn’t leave it behind now if we triedas the great Fred McDowell knew so well.

Lord, that 61 Highway, it the longest road I know

Lord, that 61 Highway, it the longest road I know

She run from New York City, down the Gulf of Mexico

(“61 Highway Blues,” by Fred McDowell)

BLUES TOUR FACTS

Clarksdale blues festivals, clubs and juke joints:

Ground Zero Blues Club – owned by Morgan Freeman, Bill Luckett and Howard Stovall; best local talent playing in the tradition of Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and Charley Patton; featured on “60 Minutes.” 364 Delta Ave., next door to Delta Blues Museum. 662-621-9009

The Sunflower River Blues and Gospel Festival

Red Top Lounge, 377 Yazoo Ave, Clarksdale (better known as Smitty’s)

C.W.’s, 381 W. Tallahatche Ave.

Red’s Lounge, 395 Sunflower Ave.

Uncle Henry’s Place and Inn, 5860 Moon Lake Rd (20 miles n. of Clarksdale) once known as Moon Lake Casino, celebrated by Tennessee Williams in “A Streetcar Named Desire”

Places to eat:

“Chamoun’s Resthaven Café” in Clarksdale – features Lebanese, Italian and American cuisine reflecting the diversity of the Delta. (kibbie, cabbage rolls and baklava; spaghetti and lasagna; chicken-fried steak and coconut cream pie)

“Madidi” co-owned by Morgan Freeman and Bill Luckett, located at 164 Delta Ave in Clarksdale. Mixes food and fun in refurbished old building.

Shopping:

Cat Head Delta Blues & Folk Art – 252 Delta Ave. outlet for folk art by artists from Mississippi, also extensive blues CD collections, vinyl, DVDs, books, photographs and souvenirs.

Also in Clarksdale:

St. George’s Church, where Tennessee Williams lived as a child with his grandfather, an Episcopal priest, and later evoked his Delta experiences in “Cat On A Hot Tin Roof.”

For more information, check out these link sites:

Delta Blues Museum

Riverside Hotel: To “spend a night in blues history” call for reservations: 624-9163

Story by Larry Wells, photos by Ginger Hughes. Story writer and popular author Lawrence Wells lives in Oxford, Mississippi. Photographer Ginger Hughes is a grad student at Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas.