Headlines

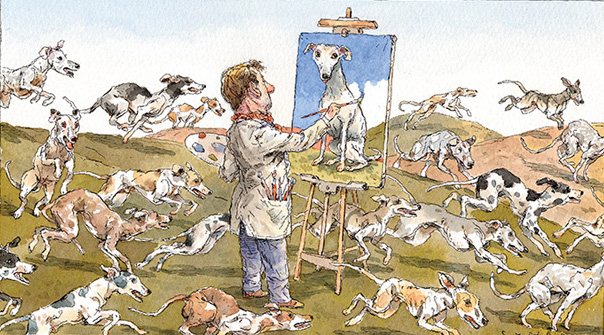

Dunlap: Artist Reflects on Dogs that Found Ways into his Work—and Heart

The last and damnedest thing a good dog will do for you is die. You know this going in, but when you’re handed a note by a four-year-old that reads, “Pleez cn I hav a dog???” you think, you hope, you pray it will be different this time.

Maybe you’ll die first.

Our daughter would certainly have formulated that request on her own, but her inscribed copy of Willie Morris’s My Dog Skip didn’t help. In part the inscription says, “Welcome to the world! Don’t read this book until you’re two years old. Get your momma and daddy to give you a dog like Skip when you’re in the third grade.”

Thanks a lot, Willie.

Hell, what did she need with a dog? I’d given her a stone marten. She adored her vintage fur complete with face and paws, the sort once so popular with 1940s movie stars. The two were inseparable. She petted, talked to, and slept with the lifeless pelt, and named it Lassie.

This could not be sustained.

From the beginning, dogs have meant the world to me in both life and art. They found their way into my work early on, mostly as metaphor, stand-ins for the frequent absence of a human presence. Delta Dog Trot—Landscape Askew is one such painting. It hangs in the lobby of Greenwood, Mississippi’s Alluvian Hotel and features a life-size bird dog. I once eased up behind a pair of well-oiled bar patrons locked in animated conversation in front of the painting. I was sure they were overwhelmed by the power of the remarkable artistic achievement before them. Instead, they were reminiscing in a highly emotional way about dogs they had owned but were now departed.

As an artist, I keep a PowerPoint presentation ever ready for museum docents, college classes, and the garden clubs. It changes from time to time, but one segment remains constant: a circa 1951 photograph of my brother and me at our makeshift lemonade stand. “5 cents a glass,” the sign reads. We are flanked by our two dogs of no discernible breed, Prince and Yellow Pup.

Later that summer and not long after the photograph was made, in the clear slow motion of irrevocable memory, I see Prince as he is hit by a car. My grandfather and I buried him in the woods behind his Webster County, Mississippi, home. I can still find the spot—and on occasion, do. To this day, I cannot get through this part of an otherwise entertaining and informative presentation without choking up a bit, as I do now.

But that is all in the past. The problem at hand was a daughter determined to have a dog. It was time for stalling tactics—research at the local library, interviews with dog owners, hours of Animal Planet programming, countless Westminster Dog Show reruns, even a visit to the kennels of a South Florida greyhound track with its owner, but alas these gorgeous, people-friendly animals were just too large. Our daughter was not fooled, and we’d begun to cave. Finally, her ever-resourceful mother found a suitable candidate online. Timbre-blue Whippets in Lexington, Virginia, had a damaged dog in need of rescue.

Timbreblue is a devoted family affair that whelp a couple of litters a year. Some of their pups had been named after things your mother admonished you not to do. “Plays with Matches” was called Ember, “Shows Her Panties” was Fanny, “Don’t Slam the Door” was Banger, and the dog that would become ours, “Blames Her Brother,” was, of course, Snitch.

It’s useful to know that the sight hound that has come to be our modern whippet originated in the north of England in the eighteenth century. This “poor man’s greyhound” was a poacher’s best friend, with quickness, agility, and speeds up to thirty-five miles per hour. The breed was adept at ferreting out rats and rabbits and excelled at “rag racing,” a straight-line contest of whippets sprinting toward their masters, who enthusiastically waved towels at the track’s end. These days owning a whippet means never again having to go to the bathroom alone.

From that initial drive home up Interstate 81 to Fairfax County, Snitch attached herself to the women in my family. She slept with my daughter and shadowed my wife’s every move while seeming to find a place of tolerance in her heart for the alpha male, me.

William Dunlap is an Ole Miss alum and artist. He can be reached at dunlap.billyd@gmail.com. Originally published in Garden & Gun.