The Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Society of New Orleans has announced the winners of the William Faulkner–William Wisdom Creative Writing competition.

Larry Wells of Oxford was awarded first place in Narrative Non-fiction for his memoir, Shakespeare’s Royal Bastard, about being hired by the University of Mississippi as ghost-writer for Gertrude C. Ford. Contest prizes will be awarded Nov. 23 in New Orleans.

Larry Wells of Oxford was awarded first place in Narrative Non-fiction for his memoir, Shakespeare’s Royal Bastard, about being hired by the University of Mississippi as ghost-writer for Gertrude C. Ford. Contest prizes will be awarded Nov. 23 in New Orleans.

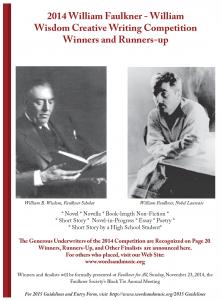

The William Faulkner–William Wisdom Creative Writing Competition is sponsored annually by The Pirate’s Alley Society, Inc, a non-profit literary and educational organization. The competition is for previously unpublished work. Self-published and print-on-demand books are considered published. Books, stories, essays, poetry previously published in their entirety on the Internet are considered published. Collections are not accepted in any category. In addition to Nobel Laureate William Faulkner, the Faulkner Society’s namesake, the competition is named for literary scholar and collector William B. Wisdom of New Orleans, shown at right, who amassed a significant collection of memorabilia related to William Faulkner. His collection is housed today in the Library of Tulane University. Mr. Wisdom’s daughter, New Orleans philanthropist Adelaide Wisdom Benjamin was among the earliest supporters and Advisory Council members of the Faulkner Society. She was an instigator in the creation of the competition and underwrote the first prize for Best Novel.

Entries are accepted in eight categories: novel, novella, book-length narrative non-fiction, novel-in-progress, short story, essay, poetry and short story by a high school student. Overall goals of the competition are to seek out new, talented writers and assist them in finding literary agents and, ultimately, publishers for their work. There were 310 entries for 2014 in the narrative non-fiction category. Of that total, 146 entries were from Louisiana authors. The remainder of the entries represent 32 states and eight foreign countries.

The narrative non-fiction category was judged by Deborah Grosvenor, who has more than 25 years’ experience in the book publishing business as an agent and editor. During her career, she has edited or represented several hundred nonfiction books. As an editor, she acquired Tom Clancy’s first novel, The Hunt for Red October. Her distinguished client list includes nationally prominent writers, New York Times bestselling authors, and prize-winning historians and journalists. Among them are Stephen Coonts, Eleanor Clift, Morton Kondracke, Thomas Oliphant, Charlie Engle, Harrison Scott Key, John Sexton, Henry Allen, Aaron Miller, Scott Wallace, Curtis Wilkie, Bob Guccione, Nina Burleigh, Thomas Fleming, Jonathan Green, Jay Rubenstein, Willard Randall, Mark Geragos, Peter Cozzens, Meg Noonan, Barbara Dreyfuss and Elizabeth Pryor. Deborah is interested in narrative nonfiction in the categories of history, biography, politics, current, and foreign affairs, memoir, food, the South, humor, Italy, the environment and travel. For fiction, she is simply interested in great storytelling, especially in an historical context. Deborah is the recipient of the TWIN award (Tribute to Women in Industry), given by the YWCA and industry to “outstanding women who have made significant contributions to their companies in managerial and executive positions.” She has been a part of the Faulkner Society’s annual fall festival since Word & Music was created and regularly judges a category of the Faulkner-Wisdom Competition.

Winner: Shakespeare’s Royal Bastard, by Lawrence Wells of Oxford

Winner: Shakespeare’s Royal Bastard, by Lawrence Wells of Oxford

Equal Runners Up: Stronger, by Mary Bradshaw of Flowood; The Red-Headed Jewess of Oxford Road: You Can’t Imagine This Life, by Cindy Lou Levee, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

In summarizing Shakespeare’s Royal Bastard, judge Deborah Grosvenor wrote, “Part memoir, part literary mystery, part an examination of what constitutes fiction vs reality, this is the charming, often humorous account of a writer hired by the University of Mississippi to help a wealthy elderly woman write a book proving Shakespeare’s true identity in exchange for her large donation to the school. The author seamlessly weaves together several stories in this book: his evolving relationship with his eccentric patron and his own family, his search for the ‘real’ Shakespeare, and the bawdy Elizabethan narrative he writes for his benefactor. The stories all work together and keep one turning the pages until the surprising but satisfying conclusion of this tender memoir.” Says Wells, “I’d like to thank the University of Mississippi, and especially Robert Khayat, Jane Stanley, and Don Fruge. My job as ghost-writer was to dramatize the life of Edward de Vere and his alleged affair with Queen Elizabeth⎯but writing was only half of my duties. Mrs. Ford was obsessed with proving that Edward de Vere was Shakespeare and believed, truly believed, that she was Queen Elizabeth I-reincarnated. Before we’d co-written the first page she’d cast me in the fantasy role of Edward de Vere, Lord Great Chamberlain under Queen Elizabeth I and according to legend her lover. A ghost-writer is at various times collaborator, editor, confidante, psychologist and psychic. I’m not exactly known for my diplomatic skills but luckily it all worked out. I think of Mrs. Ford every time I play with the Ole Miss symphony at the Ford Center. My sincere thanks also to Ms Grosvenor and the Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Society.”

Below is an excerpt from Wells’ memoir, Shakespeare’s Royal Bastard. The year is 1987. The author, 45, has been hired by the University of Mississippi to ghost-write a novel for Mrs. Ford, 80, a patron of the arts in Jackson. Her novel is about the theory that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, was Shakespeare. In the opening scene Mrs. Ford gives Wells a tour of her home. They banter back and forth, creating rapport and establishing boundaries.

Waiting for Mrs. F to pop the question⎯Who do you think Shakespeare was?⎯reminds me of my first teaching interview. It’s 1966. I’m twenty-five, fresh out of grad school, the ink not dry on my M.A. degree. The president of Murray State University is telling me his life’s story. He coached basketball at a rural high school. After he was promoted to principal, he continued coaching the team. “Why should the school hire another coach? Did you play basketball? Well, no matter. How much did the department chairman offer you? Six-fifty a month?” He leans over the desk. “I’m gonna make that six fifty-five.” And this was a respectable job.

Take the ghost-writing gig, support your family, pay the college tuition.

Exiting the boudoir she takes me into the sitting room. Like the rest of the house it is unheated. I’m shivering in my sports coat. On the table is a stack of papers neatly arranged⎯my resumé, clippings of reviews, samples of magazine articles. A picture on a book jacket gazes at me in reproach. I was youthful and cocksure then. “I have emphysema,” she says. “Did Jane tell you?” She coughs and hacks.

“Sorry to hear it.” There’s no putting off the other debilitating issue. “So who do we think was Shakespeare?”

“It sure as hell wasn’t the man from Stratford!” She coughs up phlegm, spits into a handkerchief, and launches into a history of Edward de Vere. Born in 1550, he was the son of John DeVere, bachelor degree at Oxford University, master’s at Cambridge, law degree at Gray’s Inn; began writing poetry and drama, a Renaissance Man who composed plays, poetry, music, Queen Elizabeth’s Lord Great Chamberlain in charge of staging entertainments at court. His family crest featured a lion shaking a spear. His contemporaries called him “Spear-Shaker.”

Like cannon balls she stacks the names of authors opposed to the orthodox view. Charles Dickens, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Mark Twain, Sigmund Freud, John Galsworthy, and Ralph Waldo Emerson had doubts about the actor and playwright, Will Shaksper (she spells it Shaxper; I spell it Shaksper). Henry James considered Shaksper one of the greatest hoaxes ever perpetuated on an unsuspecting public. Mark Twain said, “Shall I set down the rest of the Conjectures which constitute the giant Biography of William Shakespeare? It would strain the Unabridged Dictionary to hold them. He is a Brontosaur: nine bones and 600 barrels of plaster of paris.” She explodes in mirthless laughter, then continues, “It was Sigmund Freud who said, ‘The name William Shakespeare is most probably a pseudonym behind which there lies concealed a great unknown.’”

She has the whole of it by heart. Elizabeth the First was head over heels in love with Edward de Vere until he began writing poetry that she considered treasonous. “Naturally he wanted credit for his work but Queen Bess wouldn’t allow it. She was prob’ly the one who came up with the pseudonym, ‘Shakespeare.’ She couldn’t risk Oxford’s signing his own name to the sonnets, because after Shakespeare dedicated The Rape of Lucrece to Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, everybody knew Henry was their son.”

The proverbial light goes on: 1) Southampton was the ‘Fair Youth’ of the sonnets; 2) Shakespeare wrote sonnets which hinted that the Fair Youth was Elizabeth’s illegitimate son and unacknowledged heir; 3) denied his birthright, Southampton joined the Essex Rebellion and tried to seize the throne by force.

“Sonnet One-Twenty-Seven,” says Mrs. F, in her fervor no longer short of breath, “tells of a child born in the shadows, a black prince who does not bear Beauty’s name. The poet demands that ‘Beauty,’ or Queen Bess, acknowledge their son.” With a hand to her chest, she rasps:

In the old age black was not counted fair, If it were, it bore not beauty’s name; But now is black beauty’s successive heir, And beauty slander’d with a bastard shame.

Then she launches into an oration about “The Book of Babies,” a list of royal bastards circulated among the crown heads of Europe. She also is fascinated with a Shakespearean scholar named Percy Allen, who held a séance and claimed that the ghost of Edward de Vere confirmed that he was Shakespeare, and that Queen Elizabeth secretly gave birth to their son, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton.

Out of the blue, a blazing non sequitur. “I’ve picked out a title!” She flashes a neon-bright smile. “‘Shakespeare’s Royal Bastard.’ How do you like it?” I scribble SRB dutifully in my note pad and hear myself saying, as if from a tape recorder with bad batteries, “Uhhh, it miiight wooorrk.”

“Does the world need another book about Edward de Vere?” I can’t believe I said this. My impertinence has her gasping for breath, spittle flying, long red nails stabbing the air. Seeking a familiar target, she rails about her failed stage play, “Shakespeare and Elizabeth Unmasked,” having been ignored by the Oxford “in-crowd.” She didn’t expect praise, didn’t aim that high, but they could have given her an A for effort. What had any of them done besides write a monograph? “Goddamn prima donnas!” I scribble on my pad: Who are the prima donnas? She shoves a self-published playbooks across the coffee table. It is inscribed to me. The meaning is clear. We’re going to send the prima donnas to hell.

Anonymity is looking pretty good to me. Otherwise, some wag seeing our self-published volume gathering dust might be tempted to write “R.B.” after my name. What if I used a pseudonym? Ronald Bragg, Ralph Boozer, Richard Blunder. I make a note to read the small print in my contract.

None of Mrs. F’s material is original. She read J. Thomas Looney’s “Shake-speare” Identified” and stole his playbook. The real story I perceive now, sitting in her cold, dusty house, is one of loneliness, longing and thwarted desire. She is King Lear’s fourth daughter, the one born in secret. To her, Edward de Vere not only is Shakespeare but abides in this house, this room, wherever she goes. As Satan says in Paradise Lost, “Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell.” De Vere could be standing beside the coffee table, a gold toothpick in his mouth, casting a sardonic eye on this rich dilettante eager to shuffle off the coils of anonymity, and me, her hireling, a middle-aged writer gambling his career on a theory about which he knows very little. What would de Vere say? Go forth, sweet fanatics, and tell the world that I am he who wrote the sonnets and plays, not that other with “little Latin and less Greek.”

Mrs. F falls on the Danish sofa. Not being able to breathe makes her furious. With faltering hand she indicates the clippings. Stabbing them with a stiff index finger she makes a da-da-da-da-da sound until I say, “You read my reviews?” She nods, silently raging. In a flash of irony I realize that these overly generous reviews are what damned me.

She heaves air into her lungs. “Good reviews don’t guarantee a bestseller. I want our book to be as lascivious as can be!”

Make Shakespeare a stud? I was expecting different marching orders. Take the hill, give no quarter, drown the prima donnas in their own blood. A hundred and fifty miles away, my wife, who knows about the perils of a literary career, is waiting to hear about this meeting. When I get home I’ll ask her about the degrees of lasciviousness. Should we start quietly and build up (I mean, me and Mrs. F), or pile on sex from the get-go? If Dean doesn’t know she’ll have an informed opinion. With any luck, the book will be rejected by first-tier readers at Doubleday and Random House. There’s no shame in writing an un-publishable ms. Fitzgerald and Faulkner hacked out Hollywood scripts never made into movies. My job is to hotwire a plot without being electrocuted.

When she invoked her husband’s nicotine presence and gave me a peek at her diamonds, she was saying I am Elizabeth Rex. You are Edward de Vere. My husband is dead. Let’s get it on. She is all the heat this house needs, a built-in furnace, a hottie that refuses to yield to age, a pink fortress on a blue-chip mountain. Was Edward de Vere really Shakespeare? I don’t know⎯but if in the weeks and months to come, de Vere comes creaking and clanking to life from my typewriter, no one will be more surprised than I. In a way he and I are brothers in the bond, twin sons of Mrs. Frankenstein.

“He was a virgin!” Her eyes are like rapier points.

“Excuse me?”

“Edward de Vere, whoja think!” My forward understanding makes her furious. I struggle to catch her drift. “I mean,” she says after she calms down, “he was a virgin when Elizabeth seduced him.”

“She seduced him and not the other way around?”

“She’s the queen. He lives to satisfy her.”

We’re all virgins in the early going, but Shakespeare/Edward de Vere a virgin? Sex is the jet fuel of all creative endeavor. Think Mozart, Byron, Elvis, Warhol. Shakespeare had balls and wrote with compassion. What girl could keep her hands off him? Life was short, maidens rolling in the hay at twelve. Fourteen was pushing it. The skeptic in me can’t keep from asking, “So, you think he’d still be a virgin after attending Oxford, Cambridge and Gray’s Inn? Maids being handy, so to speak.”

She writhes in agony, heaves to get her breath, thwarted, obstructed, constricted by my lack of understanding. “He had to be careful of his seed!” Would an earl descended from Plantagenets waste sperm on a milk maid? No, he kept himself pure for a woman of stature. Meanwhile, young Edward read poetry, practiced swordsmanship and falconry, and bided his time. “That’s why he was still a virgin. Okay?” She bites into an Oreo, black eyes burning into me, waiting for me to capitulate. Sometimes the waiting can be long. Shadows grow deep. Rip Van Winkle knew this feeling. Bears and hippopotamuses know it.

Nobody dances the old dance like a southern belle. She rummages through a Holinshed’s Chronicle of Sex. Where did Oxford and Elizabeth first make love? Forget a grassy meadow under blue sky, forget balmy breezes and birdsong, forget shall-I-compare-thee-to-a-summer’s-day. Imagine instead a wintry night in March, the water frozen in the wash basin, the castle so cold you want pull the blanket over your lover and wolf around. The Elizabethan ice age was hell on pneumonia but ideal for breeding. Did the Spirit of the Renaissance just swoosh by my ear? She has no problem finding breath for her favorite fantasy. A royal progress arrives at a castle. A cloud of vapor hovers over the procession. The chattering, belching, farting throng of lords and ladies and their entourage come to a halt. Litter bearers set down their burdens. The men pee in the moat, lords and vassals alike. Ladies in waiting form a protective screen for the queen to pee. She glances up and sees Oxford shaking off his epistle, a golden mist rising from the moat and⎯ “How do you like it so far?” I stare at my note pad in disbelief. Did she actually say “shaking off his epistle” or did I make it up? Where is she going? Is peeing foreplay? She fights through a paroxysm of impatience. “All right, Smarty Pants. Let’s see you do bettah.”

Larry Wells is a HottyToddy.com contributor and can be reached at lwells@watervalley.net.