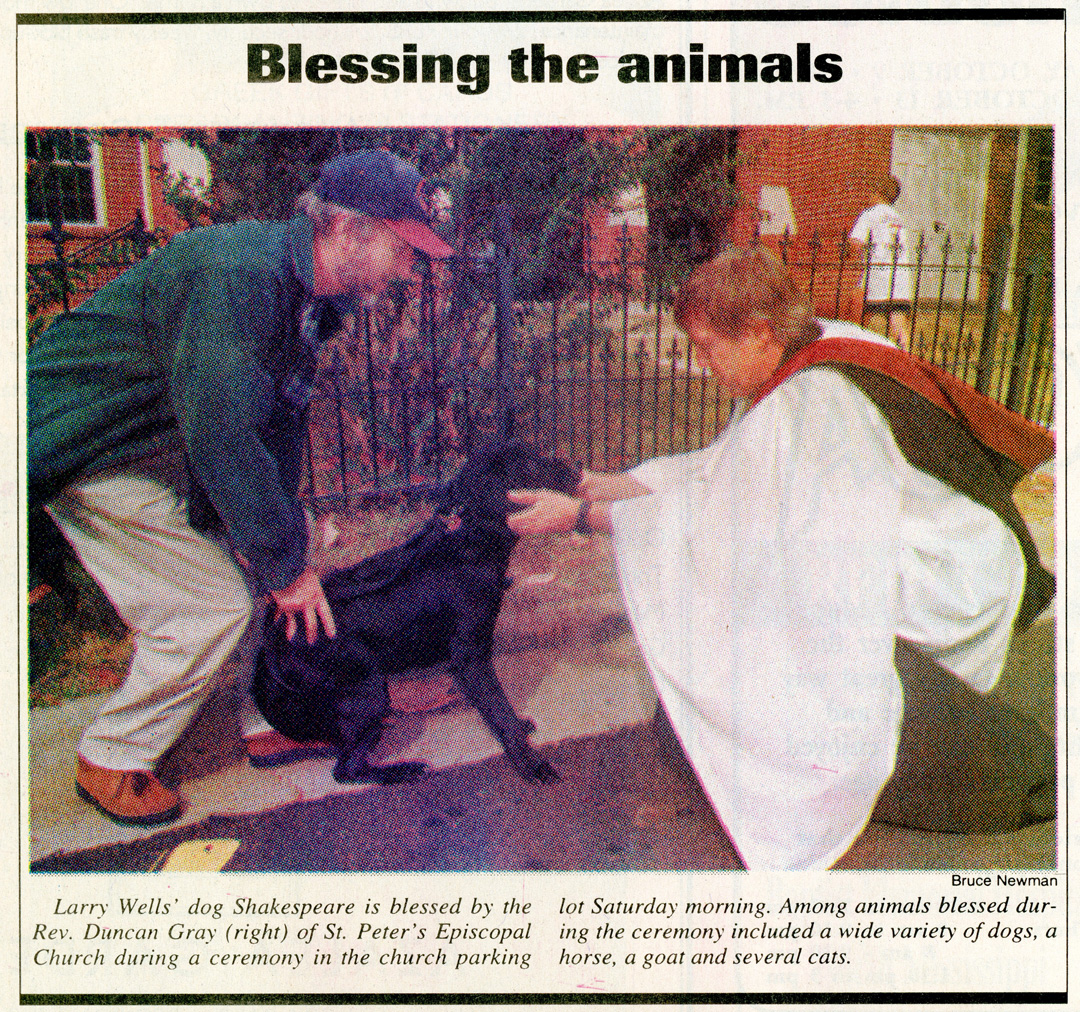

Special thanks to the Oxford Eagle for use of the graphic above.

by Larry Wells

School days, school days, Dear old golden rule days,

He was half Labrador, half Setter and all heart.

We got him from Nicky Hewlett of Taylor, who brought us four puppies to choose from. To keep them from jumping out of his pickup, he tossed in some pork bones. By the time he pulled into our driveway, the pups had diarrhea. My wife Dean was afraid to look at them because, as she said, “I’ll want all four. You pick one!” Someone once told me that you can judge a puppy’s spirit and intelligence by whether it will look you in the eye. Three of Nicky’s puppies were quarrelsome and whining − understandably so, given their plumbing problems − the fourth had a long, shining coat and immense composure. With paws extended, he lay on his belly and watched me. When I gestured for him to come to me, he came. I carried him to Dean. She hugged him, diarrhea and all, and that was that. “What do you want to call him?” she said. At the time, I was working on a book about William Shakespeare. It was a convergence of the twain.

That was June. By October, a rapidly-growing Shakespeare Wells had become King Kong on a leash. Dean could barely control him on walks. “Shakes,” as she called him, would tow her pell mell along South Lamar, stopping only to mark his territory. Although he was exceptionally intelligent and eager to please, he was a bundle of energy. We needed to get him trained to accept commands. No longer could I gesture and have him come to me. That only happened at crunch time in the bed of the pickup. I called Candice Baird, local dog trainer and breeder and signed up for obedience school. Dean was all for enrolling Shakespeare, but considered herself too indulgent to train him. This was true, though we did not dwell on it. And thus our obedience training − mine and Shakespeare’s − began.

OPENING SESSION It is Saturday. The Circle in front of the Ole Miss Lyceum is deserted. Five dog owners appear for the first session. Like college freshmen, hopeful and self-conscious, we sit on the steps of the Lyceum awaiting orientation. We talk exclusively about dogs. I learn that Shakespeare’s classmates will include two Jack Russells, a Great Pyrenees and a Weimaraner.

Trainer Candice Baird hands out a list of required items: treats for the dog, a toy or ball, water bowl and water, garbage bags for policing the area, a fanny pack, choke collar and six-foot leash. She will instruct us in techniques to pass on our pets. In effect, we are her pupils, not the dogs. To demonstrate how our dogs will benefit, she takes her distinguished German Shepherd, Nicki, through the standard drill. Nicki will come to her on command (in fact, seems to anticipate it), sits, lies down, stays indefinitely, and heels at her mistress’s side like a Siamese twin. We dog-parents sit on the steps of the Lyceum and lip-sync with Baird’s commands, fantasizing that our beloved, fun-loving but erratic frog-like puppies will obey our every command.

Obedience training is intended to build a dog’s confidence, teach it what is expected, and give structure to its existence. I raise my hand. “What,” I ask Baird, “is the hardest thing for us to learn?” “Being consistent,” she replies without hesitation. “Use the same commands every time and try not to lose your temper.” This is not going to be be easy when I’m lying on the ground and Shakespeare is on top of me, but Baird does not deal in negatives. She asks us to write down what we want our dog to take away from the class. I print in all caps: “Not to jump on me and knock me down.”

The day before Obedience School begins, I seek divine guidance. By coincidence, St. Peter’s Episcopal Church is holding its annual “Blessing of the Animals.” In the parking lot outside the church, every kind of animal you can imagine including dogs, cats, gerbils and a raccoon or two, are waiting for God. Reverend Duncan Gray bestows individual blessings on each pet. He gamely attempts to bless Shakespeare, who to my shame is backing away from grace. I put my foot against his backside and cut off his retreat. Rev. Gray prays fast. “Shakespeare-you-are-precious-in-God’s-sight!”

Amen.

LESSON ONE Dean waves goodbye as I back the car out of the driveway. Her baby is going off to college. The owners gather in the Grove on the Ole Miss campus. Grey squirrels bark at our puppies, who strain at their leashes though without rancor. The Jack Russells establish themselves as most popular. “Jack Daniels” is four months old; “Abigail” eight months. “Cotton,” a dignified five-month old Great Pyrenees, has his sights trained, no doubt, on the horizon. “Brantley,” a one-year-old Weimaraner, is the alpha dog. Shakespeare strains to get at the Jack Russells. You’d think he was running for class president. I am taken aback when Baird asks me to have Shakespeare demonstrate the “down” command. I have no idea why she has chosen me. Maybe she sees something in Shakespeare I don’t. You’re up, Shakespeare, get with it.

Baird instructs me in procedure. I listen hard. The way to make your dog lie down is to offer a treat, lower it to the ground so that he follows it down with his head. As he leans over, put gentle pressure on the back of his neck and assist him in lyinge down. To my surprise Shakespeare slumps on his belly. Dean would be so proud. As the leaves rustle overhead, resplendent in fall colors, the owners attempt to duplicate our miracle. “Down, down-down-down!” they say and slavishly pass out treats. Cotton is pleasantly aloof. Nothing bothers a Great Pyrenees. The Jack Russells yank at their leashes paying Jennifer Yancy and Colleen Houlihan scant attention. Brantley the Weimeraner, son of Suzie Shannon, is best in class. He will sit or lie down or come when she calls, all the while glancing about with enigmatic yellow eyes.

Baird explains that each breed reacts differently. Jack Russells are independent-minded and have to be coaxed. Unless you make a game of the training they may rebel. Great Pyrenees are sensitive. If you’re not tactful their feelings may be hurt. Weimeraners are quick learners but often stubborn. They like a calm, patient master. (I’m noticing how calm Suzie Shannon is.) A mixed breed like Shakespeare is a lovable question mark. I have no idea which behavior I’ll be getting − a Lab’s eagerness to please or a Setter’s laissez faire.

LESSON TWO − SIT AND STAY The dogs greet each other in lively fashion and gnaw at their leashes. Cotton has outgrown his choke collar and is in need of a Paul Bunyan upgrade. Abigail is in a blue funk and growls at her classmates. Brantley and Shakespeare begin tussling and ensnarl their leashes. Baird greets each dog and praises them for their attendance. We start by reviewing what we learned at the last class. I give the “Down” command. Shakespeare requires multiple treats to jog his memory. We make a circle and order our charges to lie down and remain still. Shakespeare lies down, twists his head, and watches me walk around him. His almond-shaped eyes seem to take pity on me. The other owners are saying Stay, stay. Some dogs rise, some fall.

At the end of the lesson Baird tells us we did well for the most part. “Remember, practice makes perfect!” she calls as we lead our pets away.

LESSON THREE − HEEL Heel is a foreign concept to all dog, pulling on the leash their greatest joy. Shakespeare is accustomed to towing. Seeing that I have no chance of getting my dog to heel, Baird takes over. She jerks Shakespeare’s choke collar once. “Heel. Good boy, good boy!” Immediately he comes to heel on her left side. What is this! The only way I can achieve the appearance of heeling is when I myself heel to Shakespeare by walking on his right side.

There are distractions, I tell myself. Get a load of that blue-jay. What a racket! Fall leaves are drifting past the dogs. No wonder they can’t concentrate! At recess our dogs lap their water noisily. Foreign dogs come to investigate. Their owners have let them off their leashes. A couple sit in on today’s class, furry truants ignorant of their ABCs.

Baird puts out four cones about thirty feet apart. This is the dreaded “Cone” test, not unlike parallel parking. We are to have our dogs heel and walk a four-cornered pattern. “Keep a loose leash,” she admonishes. “Don’t drag them around.” Knowing today’s lesson was a challenge, Dean sent us to school with the most expensive dog treats at Kroger’s. Pound for pound they’re more expensive than filet minion. I don’t consider this a frivolous expense. Shakespeare heels to the treat I’m holding against my hip. “Keep a loose leash!” Baird calls alertly. From a short distance away it is supposed to appear that he’s coming to heel. The trouble begins when we round the first cone. Shakespeare keeps going. “Look,” I tell him “I heel on your right side like a good master. Give me a break!” By the fourth class the dogs are old pals. Hi, Abby, Hi, Jack Daniel. Sniff any hydrants since last time? How’s your owner? He’s crazy if he thinks I’m going to down-stay! And they bark uproariously.

Examination day is a couple of weeks away. The owners know only too well what their pets will or will not do. Shakespeare has yet to heel, or to sit when we come to a corner (I.e., simulated traffic light), or even to come every time I call. He doesn’t like being tied to a bench while I hide behind a tree. This training is to get a dog to remain calm in his owner’s absence and not bark at strangers. Any more skills, we complain out of Baird’s hearing, and our pets will deserve master’s degrees.

POP QUIZ Will our dogs come when we call? Distractions abound. The Jack Russells discover squirrel scent in the grass or something better. Obedience School has a way of bringing out owner panic. We collapse into dog-speak. Endearments ordinarily whispered in a pet’s ear become common currency. Sweetiebutt, Precious, Cuddlebumpkins, Doodlebug, Punkin-doodle, Sugarlumps, Scooterbaby, Youza goodygoody doggie-dog-dog! Abigail takes her time, walking a crooked mile to Yancy. Jack Daniels runs toward Houlihan, then stops and furiously tracks a scent. The Great Pyranees, Cotton, is somewhere on a snow-capped mountain somewhere between France and Spain. Only Brantley comes on command, approaching Shannon with the hip-wagging saunter of a pointer.

At home, Shakespeare comes when I call as long as he doesn’t have something better to do. I walk him to a designated spot, have him sit and stay, then back up twenty paces. “Come, Shakespeare!” I command. Everybody grins in anticipation of seeing me flattened. Shakespeare lays back his ears and charges at full speed. I hold a treat at waist level, though his vision is so good that even while running he sees everything. At the last second he skids to a sitting position and claims his reward. “Ooooh” go the owners. My armpits are soaked with sweat. My attention span is shot. “Pet him every time he obeys,” Baird re inds me. “Youza good boy,” I say sincerely.

The key to success is repetition. This week’s homework is to make our dogs do a down-stay for twenty minutes. Baird suggests that a good time to do this is while watching TV. I raise my hand and share a true story about Shakespeare standing in front of the set when “Lassie, Come Home” came on. Baird suggests practicing down-stay when his favorite show is not on.

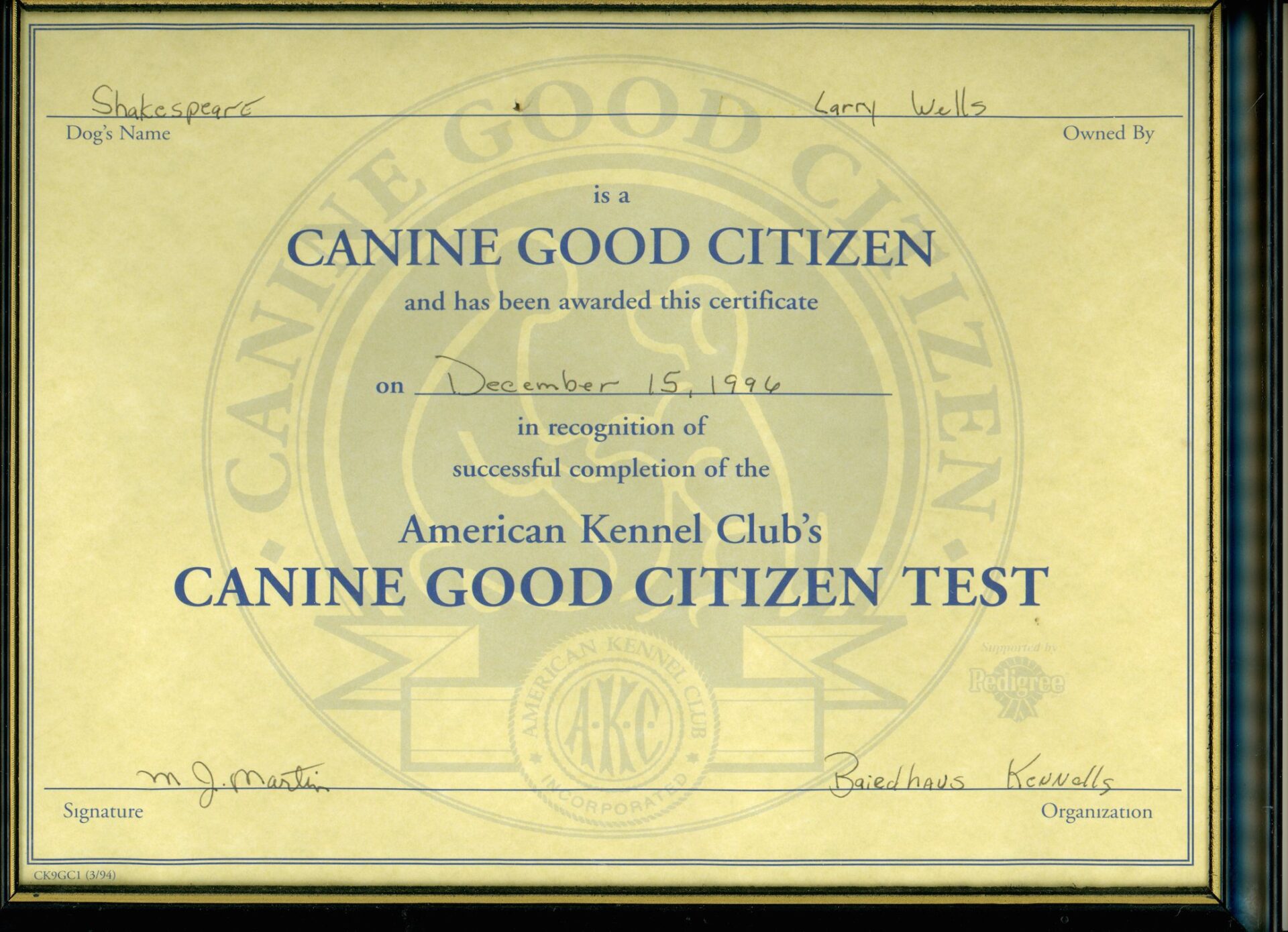

FINAL EXAMINATION The dreaded day arrives. Dean is beside herself with parental concern. Will Shakespeare come when I call him? Will he hold a down-stay while the examiner distracts him by hammering a pot with a metal spoon? Will he pass his Canine Good Citizenship Test? Dean follows us out the driveway, waving goodbye. As I drive to the campus I have no idea that she is sprinting up University Avenue after the car. The parking lot across from the Ole Miss baseball stadium is today’s testing location. It is the first cool day in November, when you sense a shifting of the seasons and a hint of things to come. The owners wish each other good luck, none having a clue how Sugerlumps/Scooterbug will perform. At first, my dog tries to play with Brantley and Abigail. He’s no longer campaigning for president but has settled for class clown. Though Baird told us not to bring treats, our fanny packs bulge with forbidden goodies. Unaware that Dean has sneaked into the front seat of the car and is watching over the dashboard, I prepare to put Shakespeare through his paces. Baird has arranged for Jeanette Martin, a certified examiner, to administer the American Kennel Club test. Like first graders conditioned by repetition, we line up our pets in their accustomed order. Voices ring out across the parking lot: “Heel, Jack Daniel!” − “Down, Cotton!” − “Stay, Shakespeare!” This is the moment of truth. When I say “come” I don’t want him taking off like Michael Jackson in slam-dunk trajectory. Amazingly, he settles down and obeys every command until the test when the owner commands his pet to stay and leaves. The purpose, as stated earlier, is to see if the dog will remain calm in his owner’s absence. Martin ties Shakes to the bumper of her van. I hide behind a tree, not knowing that Dean is watching intently, her heart in her hands. Then the unexpected occurs − the van’s rear hatch accidentally slams shut with a resounding crash − Shakespeare goes berserk, struggling at his tether and trying to get away. I rush over to calm him. Martin says, “No harm, no foul. It‘s not your pet’s fault.” A few minutes later Martin checks the test scores. To my great relief, Shakespeare has passed, along with all of his classmates: Jack Daniel, Abigail, Brantley and Cotton. We pet each other’s dogs and exchange high fives. Baird congratulates us, handing out “Canine Good Citizenship” diplomas.

Now Dean comes bounding out of the car. She can’t wait to hug her baby. For her, these past eight weeks may as well have been eight years. He’s gone through pre-med, medical school, and internship. He’s a doctor of the heart, a psychiatrist of the soul, a therapeutic lifetime companion, a bona fide Obedience University alumnus. We celebrate by walking the distinguished graduate around the neighborhood. At first Shakespeare heels as he has been taught. Then somehow he gets loose and runs toward busy South Lamar Boulevard. Giving up any thought of catching him, I can only kneel and call, as calmly as I can, “Come, Shakespeare!” Silhouetted against the glare of headlights, he stops and looks at me over his shoulder, a big, good-natured mutt poised on the edge of disaster. He has no idea what cars are, or that they will not stop for him. I call again, trying to keep the panic out of my voice. I don’t know what instinct makes him obey. Maybe he enjoys showing off his new skills, maybe the Call of the Wild is not for him, maybe I’m worth coming back to. Whatever the reason, when he trots toward me, panting with that big, wide grin, that’s when I know I’ve graduated, too.

SOME DO’S AND DON’TS OF OBEDIENCE TRAINING

Do: 1. Praise − teach by motivation with treats and praise. 2. Practice − only through repetition will your pet learn what you want. 3. Patience − dogs learn at different speeds; don’t work with him when you’re frustrated or tired. 4. Consistency − never vary the commands. 5. Correction − some dogs are stubborn and need firmer leash control.

Don’t:

1. Don’t forget to praise or reward your dog for good performance. 2. Don’t make the dog too submissive by being too harsh with him. 3. Don’t be unpredictable with punishment; it should be impartial and consistent so that the dog understands what it is doing wrong and why.

—————————————————————-

Lawrence Wells is a frequent contributor to Hottytoddy.com. This story originally appeared in SW Airlines Spirit Magazine under the title “Bark Victory.”