July 4, 1976: The square is quiet in the early morning.

A five-knot breeze stirs the oaks beside the Lafayette County courthouse where, in a very short time, a balloon will take off to honor America’s 200th birthday. A slender, dark-haired young woman dressed in a striped T-shirt and jeans sits on the courthouse steps and waits for the balloonists to arrive. She is Dean Faulkner Wells, daughter of William Faulkner’s youngest brother, also named Dean. While she waits, she recalls her grandmother’s story about Oxford’s first balloon ascension in 1905.

The crew, a tall, gangling black man and a surly, unshaven white man, arrive without ceremony on the square, hitch their wagon, and haul out a dirty, folded canvas canopy, ropes, stakes, and cordwood. Onlookers begin to gather as the black man selects a spot in the center of the unpaved street that circles the courthouse. After he digs a fire pit, he begins to lay a fire. The white man, likewise, makes his preparations. He gets out a jug of corn whiskey and begins to drink.

In their house two blocks from the square the Falkner* boys — William, 8, Jack, 6, John 4 — slip out the kitchen door, escaping their mother’s watchful eye, and hurry to town. Their adventurous spirit is rewarded by the sight of an enormous grayish-black canvas bag being laid out and attached by ropes to stakes set in a circle. In the center a fire burns briskly. The Falkner boys watch the black man pour coal oil on the fire and the white man drink from the jug balanced on his shoulder. Most of the thick black smoke blows into the eyes and throats of the spectators, though some of it causes gentle billows within the huge bag.*

A rainbow-hued Volkswagen van with “Hot Air, Inc.” painted on the side circles the courthouse twice before it stops. Dean goes over and introduces herself to the pilot, Lin Stanton, of Greenwood, and his brother, Mark. With a smooth complexion that makes him look younger than his 28 years, Lin checks the wind. He advises us (I’m there, too!) that he intends to file a flight plan and time of departure with the Oxford-University Airport. He doesn’t want to take off any later than 9:30 a.m. When Dean says this is her first hot air flight he asks, “Are you going to be OK?”

“Certainly, why shouldn’t I be!”

“Well, sometimes,” he says, a bit taken aback. “I’ve seen women panic.”

“I wouldn’t say that too loudly,” Dean says, adding with a straight face, “Some of my best friends are women.”

“Is anyone else riding?”

“Just my husband. Don’t worry, I’ll vouch for him.”

Stanton turns to the serious business of assembling the gondola and inflating the 77,500 cubic foot, hot-air balloon. Stretched out on the ground, Miss Cotton is some 70 feet long. Its material is rip-stop nylon, decorated in black, yellow, green, red and white. The Stanton brothers attach an aluminum frame which holds two liquid-propane tanks. The flight equipment includes a temperature gauge, altimeter, compass, and rate-of-climb indicator. People of all ages press forward to see inside the gondola and offer assistance.

“We never have to ask for volunteers,” he tells Dean.

By noon, horses and mules have been removed from the square, partly to protect them from the blinding smoke and partly to make room for an increasing number of excited spectators to whom the choking, sooty smoke is an acceptable risk. The Falkner brothers, like the rest, are covered with greasy soot. Their faces are streaked with tears. They have never been so happy. The fire is roaring but the balloon is only half-inflated. Smoke spews through holes in the ancient fabric, and the black man, intermittently visible through dense billows of smoke, goes about calmly sealing the breaks with clothespins. Hidden in the smoke, the Falkner boys hear their nurse Caroline Barr calling them and realize that she has orders to find them and bring them home. They remain where the smoke is the thickest, keep quiet, and watch the pilot sitting on a keg. He drinks from his crock while watching the greasy smoke unfurling from beneath the canvas.

Stanton cranks a motorized fan and blows unheated air into the balloon, the first stage of inflation. A southwesterly breeze picks up and makes his job somewhat easier. Miss Cotton swells and heaves like a whale on an asphalt beach. The spectators moan in anticipation. Children creep forward and stare into the deep, red recesses of the canopy. Dean crouches alongside them and peers inside. Her freckle-faced son, Jaybird, says, “Can I go in it, Mom?”

“Not right now,” she says. Gasps are heard when Lin disappears inside the balloon to tie canopy-release sashes to their tabs. When he emerges, he yells, “Get back! I’m going to heat her up!”

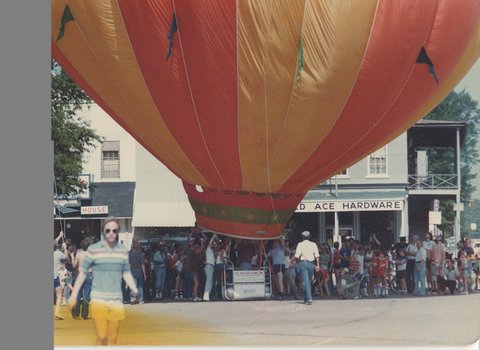

Stanton eases into the gondola, which now rests on its side. He tugs on the blast valve sending a 20-foot flame roaring into Miss Cotton. The canopy ceases lolling about, sits up, and takes notice. Onlookers fall silent as Miss Cotton rises, expands, lifts, and stands with perfect posture. (Imagine a plus-sized maid of cotton filling out a dress.) A sudden gust tilts what is now a four-stories-high balloon, making it brush against the nearest spectators, who leap aside with shrieks of happy alarm. Police officers grab the gondola and anchor it. Stanton gives the valve another short blast. Miss Cotton rights herself and steadies.

Some of the smoke swirling in voluminous clouds around the canvas balloon has actually gotten inside it, and soon it begins to sway and tug at the restraining ropes. The pilot’s assistant attaches a large, flat “basket” to the balloon with four ropes. He gently persuades the pilot to get aboard with his crock. In the process the basket dips too close to the fire, and one rope is burnt in two. The basket cants precariously to one side, with the pilot lying on his back, holding on with one hand and drinking from his crock with the other. The balloon strains at its ropes; the Faulkner boys are rigid with anticipation. The pilot puts his jug down long enough to yell, “Cut, dammit, cut!”

The pilot’s assistant whirls into action. Through the dense billows of smoke, the Falkner brothers can see him dashing feverishly from rope to rope. They hear the “thunk” of his ax. Their heads tilt back at the sight of the balloon miraculously rising. They hear the pilot cursing the canting basket. Borne on a gentle breeze from the north, the craft barely clears the buildings on the south end of the square. The three brothers exchange an electric stare of recognition. The balloon is headed straight toward their home.

“Let’s go!” Stanton says.

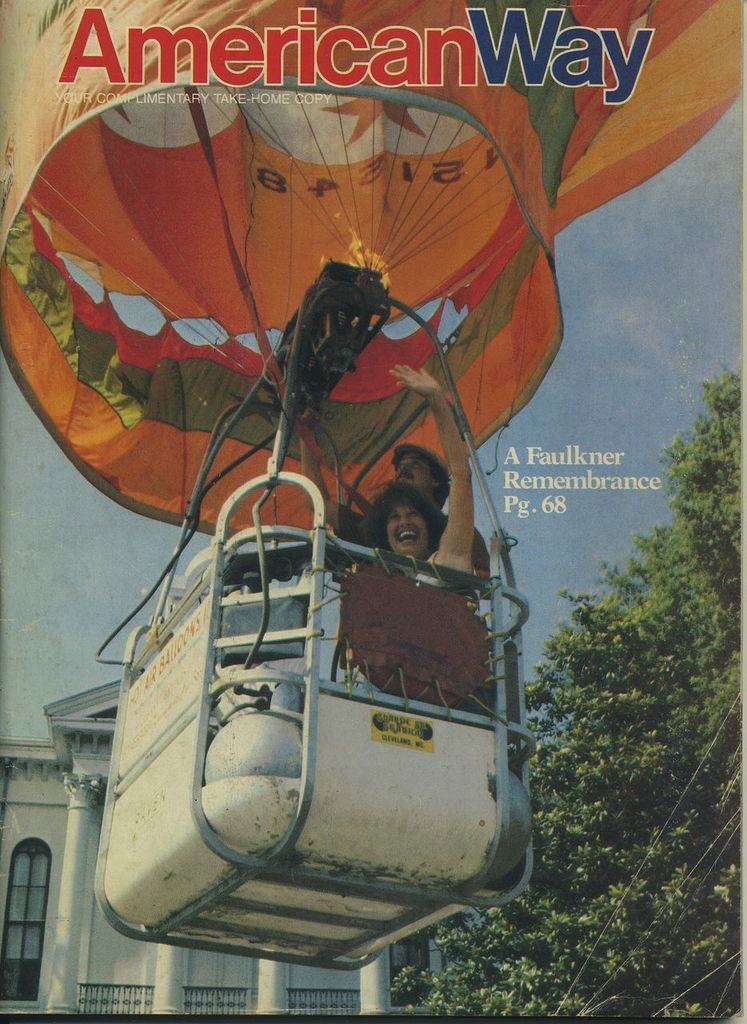

Dean climbs into the gondola [followed by the author]. People surround the balloon with mixed emotions—curiosity, disbelief, fear, delight. Stanton blasts flame heating the air inside the canopy to 140 degrees hotter than outside in order to achieve lift. “What do you want me to do?” Dean asks.

“Hold on,” he says.

Dripping sweat from the singeing heat of the burner, Stanton reaches into his back pocket and pulls out a crumpled flying cap adorned with medals, including his 82nd Airborne wings. His expression — youthful and intent a scant half-hour before — changes. He is a pilot. Around the balloon, electronic cameras are clicking with machinegun-like bursts. As if willing themselves aboard, young children raise a keening cry. Their mothers instinctively reach for them as the balloon leans under a gust, pulling the officers clinging to the gondola into the street.

“Ease up, give her some slack,” Mark Stanton calls. One of policemen lets go of the rope, and like a circus elephant balanced on a barrel Miss Cotton delicately turns a half-revolution. “Okay, turn her loose!” Stanton punctuates this command with a blast of flame. The officers fall back, and, empowered by a surge of energy, Miss Cotton lifts off, ascending at a rate of twenty feet per second. Many hands wave American flags in salute. Every face is turned upward.

The courthouse falls away quickly beneath us. Streets leading to the square expand in orderly fashion, houses and tree-lined boulevards are joined in solemn and predictable symmetry. A quick blast of flame and the gondola clears the city hall roof by two feet. The riders in the balloon could be sailing around the Horn, flying to the moon. “East-northeast at eight knots!” Stanton says.

All four of Maud Falkner’s sons were pilots, two of them professionally. She liked to say, “I don’t have a son on earth.” As a barnstormer’s daughter, Dean was born knowing the feeling of earth and gravity falling away under an ascending aircraft; but now, for the first time, my wife is experiencing lighter-than-air flight — slow, silent and altogether satisfying —and freedom from responsibilities, obligations, debts, possessions, and the passing of time.

Diminishing in the distance, now, is the white courthouse which William Faulkner called “the hub, the center.” and below us the town expands rapidly but somehow symmetrically in all directions, streets simultaneously arriving and departing from the square. Soon we are passing over St. Peter’s cemetery, its green expanse like a mirror of the town, except that instead of streets there are marbled rows of grave markers. Now we are flying over the high-school athletic fields. Sprinters call out to each other, pointing at the balloon, its round shadow darkening their surprised faces. All the while, except for Stanton’s periodic jets of flame, we move through space in utter silence and without feeling a breeze in our faces. We are the wind. “How do you like it?” Stanton asks Dean. Too excited to speak, she nods.

The Falkner boys race south after the low-flying balloon, which leaves a grey trail of black oily smoke seeping through holes in the canvas. With William in the lead they leap around the corner of Brown’s Commissary and take a shortcut through lots and gullies behind the buildings. They find they are gaining on the slow-flying balloon, but they also find it dangerous to keep their eyes on the sky while running pell-mell over uneven terrain. Skinned shins and all, they gain on the balloon and can hear the pilot, hanging on to the canted basket with one hand, talking to them between swigs at his crock. Being out of breath, they are unable to join in the conversation.

A fence blocks the boys’ way. While scrambling over it, they temporarily lose sight of the balloon behind an elm tree. William and Jack pause to haul 4-year-old John over the fence by the seat of his pants, then race at top speed to see the balloon start to descend, miraculously, into their own backyard. They cannot believe their good fortune.

“Balloon truck, this is the balloon. Do you read me?” Stanton communicates by radio with Mark, who is driving their Volkswagen van in hot pursuit. Meanwhile Miss Cotton floats serenely over the pines of Deer Run subdivision, then over the farmland beyond Campground Road. “See those treetops swirling on that hill?” Stanton observes. “That’s a thermal. Like a dust devil, it can take you up five thousand feet before it lets go.”

When the tops of tall pines brush against the gondola, Dean reaches out and touches the pine needles. Children run into a backyard, dancing on their toes, jumping up and down in Miss Cotton’s immense shadow, hands stretched to the sky. “Take me, take me!” one of them calls. “Where y’all going?”

“Montgomery! Is this the right way?” Stanton calls mischievously. Mark comes on the radio asking the balloon’s location. He is driving the van east on Highway 30, but the wind direction has shifted, and the balloon is now heading southeast toward Highway 6. Dean advises Mark to turn south on Campground Road, then east on 6. Stanton begins looking for a place to land. The uneven terrain is mostly forested hillsides with an occasional cleared field. He spots a strip of pasture a half-mile ahead. The breeze carries Miss Cotton toward what appears to be a possible landing site, but the field is looking smaller by the second. To land here is like threading twine in a needle, but having made up his mind, Stanton releases hot air and begins his descent. Below, a herd of grazing cattle see the balloon, and stampede like gazelles, alarm making them lean and nimble.

He blasts enough flame to clear a treetop, then yanks the sash causing Miss Cotton to lose altitude fast. Slipping demurely below the tree line and shielded from the breeze, she slows to about five knots. We skim low over stumps and ravines. The gondola barely clears a creek bed, then knocks down a sweet-gum sapling.

“Stand up, hold on, bend your knees,” Stanton says. Dean braces for impact, the grin freezing on her face. The gondola smacks into the steep side of a gully and is dragged sideways across the clearing. Waiting just ahead are the sharp, bare branches of a dead sycamore. It appears that a collision is imminent, but at the last moment Stanton pulls hard on the release sashes and the bright-colored canopy collapses, draping itself over the dead limbs in a sigh of relief.

In the Falkner lot, three pet ponies graze on the grass. Chickens cluck in the henhouse. The boys’ mother, Maud Butler Falkner, tends the clothesline, while their nurse, Caroline, reports that she could not find the boys on the square. The faces of mother, nurse, and ponies simultaneously turn upward as the balloon drifts over the yard. The pilot waves his crock at them, the balloon on the way down. With an oily sigh it settles on top of the Falkner henhouse and wearily collapses.

The gondola is lying on its side. Dean crawls out gingerly as if reluctant to return to earth. Lighter-than-air flight, as all balloonists know, is addictive, and just now she would rather fly than walk. She is like a Mississippi astronaut who has just gotten a bird’s eye view of her uncle’s “Yoknapatawpha,” this balloon ride indeed not unlike reading one of his short stories, when one comes away with the same lighter-than-air sensation of being released from the ordinary, of trusting in his pilot and riding the wind. When he returns to solid ground where the air is heavy with responsibility, he notices at once a change. The thrill of flight has taken residence in his heart.

A young farmer named Paul “Bear” Bryant (no relation to Coach Bryant), having observed the balloon landing, drives his tractor to the pasture and helps Stanton load the canopy and gondola. It’s hot and gnats are swarming. We are grateful for a ride to the highway.

The Falkner brothers hurry to the henhouse and slide to a halt. The pilot is rolling across the roof, holding his crock protectively high. Shingles scatter under his feet. The ponies back away, stamping their hooves. Mother and nurse are not impressed.

“This man may be hurt,” says Maud Falkner, drawing herself up to her full four feet, eight inches. Equally determined, “Mammy” Callie Barr is not in a mood to sympathize. “If he ain’t, he’s going to be!” She seizes a piece of scantling and rushes at the sky-borne invader. Before coming within striking range, she catches sight of her charges, the breathless, astonished brothers, their once-clean clothes covered with soot, elbows scratched and bleeding. The pilot uses this distraction to slide off the roof and escape. Ragged, dirty, and exhilarated, the Faulkner boys stand before their mother to receive judgment.

“There are two kinds of first-time passengers,” Stanton says. “The ones who are nervous and can’t wait for it to be over, and those who love it and can’t wait to go back up. If I am not mistaken, y’all are among the latter.” His hot, dust-streaked and thirsty passengers couldn’t agree more. Waiting for the van to arrive, Stanton turns on a garden hose and offers the pilot’s daughter a drink of water. Dean raises the garden hose in salute. “Here’s to balloons and bicentennials and people who love to fly.”

Notes:

*William Faulkner put a u in his name around 1919; until that time, the family spelled it “Falkner.”

*Source: William Faulkner of Oxford, by Murry C. “Jack” Falkner, William’s younger brother.

Larry Wells is a frequent contributor to HottyToddy.com. This article first appeared in American Way, the in-flight magazine of American Airlines.