Arts & Entertainment

Meredith and Me — Together Again

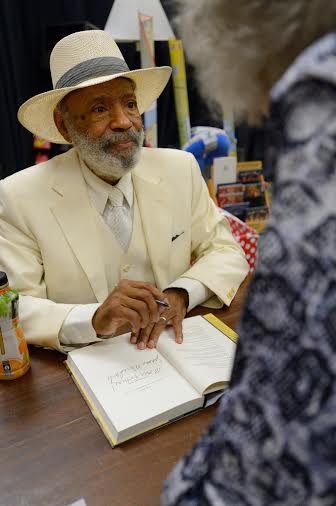

I spoke to James Meredith this week.

We go back a ways He was in his room on campus asleep and I was running around The Grove watching the standoff between the U.S. Marshals and the crowd just before the so-called insurrection ignited. Most just stood back and watched events unreel that Sep. 30, 1962. Unfortunately, two men died that night and their deaths have never been explained. I believe I know what happened to them, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

I recently wrote a book about that night, UNDER FIRE AT OLE MISS. (See Amazon.com.) Meredith is a big part of it, and so is Ross Barnett Jr., son of the late governor who challenged Meredith’s admission to the all-white university.

“I love Mississippi! I love Mississippi!” I can still hear the old governor on WELO in Tupelo riling up the admiring crowd at the Ole Miss-Kentucky football game on the Saturday night before the riot. Roll with Ross!

Young people today have no idea who Meredith is or what he did. He agreed with me when we talked this week. Now, let’s talk about coincidences: I was on campus on Monday, Feb. 18 when it was discovered that Meredith’s statue behind the Lyceum had been mugged, a noose placed around the neck with a Georgia Confederate-marked flag looped around it like a cape. Two young punks were seen running away and cussing blacks.

My wife and I left Ole Miss shortly after the1962 riot and I spent the next many, many years roaming the country as an itinerant reporter and editor. Don’t get me wrong; I had some damn good jobs! Even if many Northern colleagues acknowledged quietly: “He’s from Mississippi, you know.”

I learned much of what I know about writing and journalism, including photography, from the few valuable months I spent at Ole Miss. I loved the place! But I had to go. I needed a job.

I put the riot in the back of my in my mind for many years. Not too long ago I began to wonder if the shooters on campus were ever identified. Somebody shot at me and my buddy Jack Bowles. The FBI even came to my house and interviewed me. I couldn’t tell them a damn thing.

I began searching for information. To my surprise nothing significant had been written about the actual riot. No killers, no suspects and very little interest. What happened to the investigation?

In December following the riot, the FBI gave up. After two months. They were forced by law to turn the murder case over to Lafayette County Sheriff Ford, who happened to have been president of the local White Citizens Council. Years later I called Meredith and asked for an interview. We talked for several hours in his home. That conversation started my quest for more answers.

The entire interview — very rough language — is printed in its entirety in the new book. (Did I mention Amazon.com?). Meredith’s point was that Governor Barnett was a friend to blacks and he knew that Kennedy and Barnett had arranged for troops to come riding to the rescue. “If I had not known that, I would never have been there,” he told me. Meredith is no idiot.

When I recently called the local sheriff, Buddy East, and asked him about progress in the investigation, he said politely but quite frankly, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Crap! More work. More interviews. More research. I ordered and read the entire 3,000-page FBI investigative report.

There’s enough sloppy work by the press and the federal and state agencies to go around, with a lot left over. Perhaps they will say that about my efforts.

When I read in The Daily Mississippian this week about Meredith’s statue, I wondered how he felt about it. We talked for a bit about the distant past and I asked about the “lynching” of his statue.

“The last lynching of a black man was in 1958,” he said, and then I was turned into the interviewee. “And why was that?” he asked. I had no answer. The times have changed, I said. “And why is that?” Well, perhaps we have grown a bit. Did I really say that? I tried to come up with other responses: We don’t have those racist, lawless lawmen today; and people won’t put up with it now…etc.

Why has it changed? And has it really changed that much? He wanted me to talk about that. I tried to be honest. I told him I have driven by many elementary and high schools in Mississippi where there are still crowds of students, blacks in one group and whites in another. I spoke about Louisiana and some parts of Mississippi where blacks were imported to pick cotton, and the cotton left, and they are still there, poor, struggling, trying to scrap out a living. Quo Vadis?

“I’m mad as hell that Ole Miss and the authorities are making a mountain out of a molehill about this thing,” Meredith said. “The significance of this is to keep people focused on the past so they don’t have to deal with today and the future. Let this go and get on with life.”

Does he have more hope today than in the past? “I promised God that if I’m still living I will move Mississippi from the bottom to the top: black people in Mississippi will get it together faster than anyone else and will become an example for the rest of the world!”

He said this begins if “people follow and teach the 10 Commandments to the children between birth and age five. Nothing more and nothing less. It will solve 90 percent of our problems.”

The university’s alumni association has put up a $25,000 reward. “Why did they do that?” he asked. I was on the stand again: “Well,” I said, “it was an insult to you and the university.”

And then he baffled me: “You have helped me understand today more than anyone the thing that is happening at Ole Miss now.” Naturally, I don’t take notes on my own answers so I don’t remember everything I said. Was he mocking me? When they catch these delinquents, I’ll bet they are outsiders, not students. That has a familiar ring…

I hope you will dial me up again for more about this topic in my next column. And, I have a few more stories about a Mississippi journalist in far-off America and beyond. I’ve seen the elephant.

Dick Gentry was the Summer Editor of The Daily Mississippian prior to the 1962 riot at Ole Miss. He left Ole Miss shortly after the riot for financial reason and later graduated with a degree in journalism and business from Eastern Washington University in Spokane, where he was a writer for the Spokane Chronicle. His career also includes editor and publisher of The Caymanian in The Cayman Islands; executive editor of Hawaii Business Magazine; editor of Atlanta Business Chronicle and executive editor of the Birmingham Business Journal. His first job after leaving Ole Miss was sports editor of the Artesia (N.M.) Daily press, where he eventually became editor. Gentry lives in Clarkesville, a small mountain town about 50 miles north of Atlanta with his wife and fellow traveler of 53 years, Martha.

Tina Savas

February 20, 2014 at 3:26 pm

Meredith is right, but wrong too. We should be spending our time trying to improve today and tomorrow, but if we stop talking about yesterday, we won’t be able to understand ourselves any better than we ever have. “We may think we are through with the past, but the past isn’t through with us.”

Harry Bowles

February 20, 2014 at 5:27 pm

Interesting read by Dick Gentry. Hope to see more of the Meredith interviews and well as Dick Gentry first hand knowledge of the campus riots.

Alex Price

February 21, 2014 at 4:14 am

I think those who defaced the statue are very much the exception at Ole Miss and the south in general these days – hence the scurrying away and no claims of responsibility. Times are different and racism is much less overt but will likely always remain to some degree. It is like any other intellectually lazy crutch or generalization and I fear it will (as it has always) linger in the shadows of human interactions. Well written piece – think I may have to read, “Under Fire at Ole Miss” now. If only I knew where to find a copy …