I wrote this piece on the 50th anniversary of William Faulkner’s death.

At the time I was living in Boston attending graduate school and his passing made me a little nostalgic for my hometown, Oxford.

I have always considered it an honor that we come from the same hometown. In fact, I was kicked out of his home once for breaking the door to the widows walk. William Faulkner seems to have permeated so many parts of my life. I read many of his books in school growing up, his pictures hang on my walls, I even quote him on my Facebook page. Mr. Faulkner is synonymous with Oxford, Mississippi, or the City of Jefferson, or Yoknapatawpha County, or whatever you’d like to call it.

This past Christmas, my mom had some watercolors done of some old photographs of Mr. Faulkner taken by my grandfather for me and my sister. In an envelope on the back of the frame, my grandfather wrote down the story of that photo shoot. I thought today was an appropriate day to share that story.

For the record, I haven’t cleaned it up much. Any poor sentence structure is not mine (sorry, Grandaddy). I have 5 of these now famous photographs hanging in my apartment. They are probably my most favorite possessions. I spent about 2 hours scanning all the negatives last summer just so I could keep some of the prints.

So, without further ado, here is my grandfather Dr. Ed Meek’s account of meeting Mr. Bill.

Mr. Bill and Me

I don’t think I had ever heard of Mr. Faulkner until I enrolled at Ole Miss in the fall of 1958. My English teacher, Ms. Mildred Topp, herself a noted author, introduced her students to Mr. Faulkner’s work and from that time, I set a goal to meet the man known as the greatest writer of fiction of the 20th century.

I would see Mr. Faulkner learning on a parking meter or a bench at the Courthouse, but I did not dare speak to him. I had heard stories of how he could not be approached and I thought it was because he was mean or something. Years later, I realized it was the community’s effort to let their most famous son have a private life in his hometown. But for me, I was scared to death of him and would walk a different direction for fear I might bump into Mr. Bill.

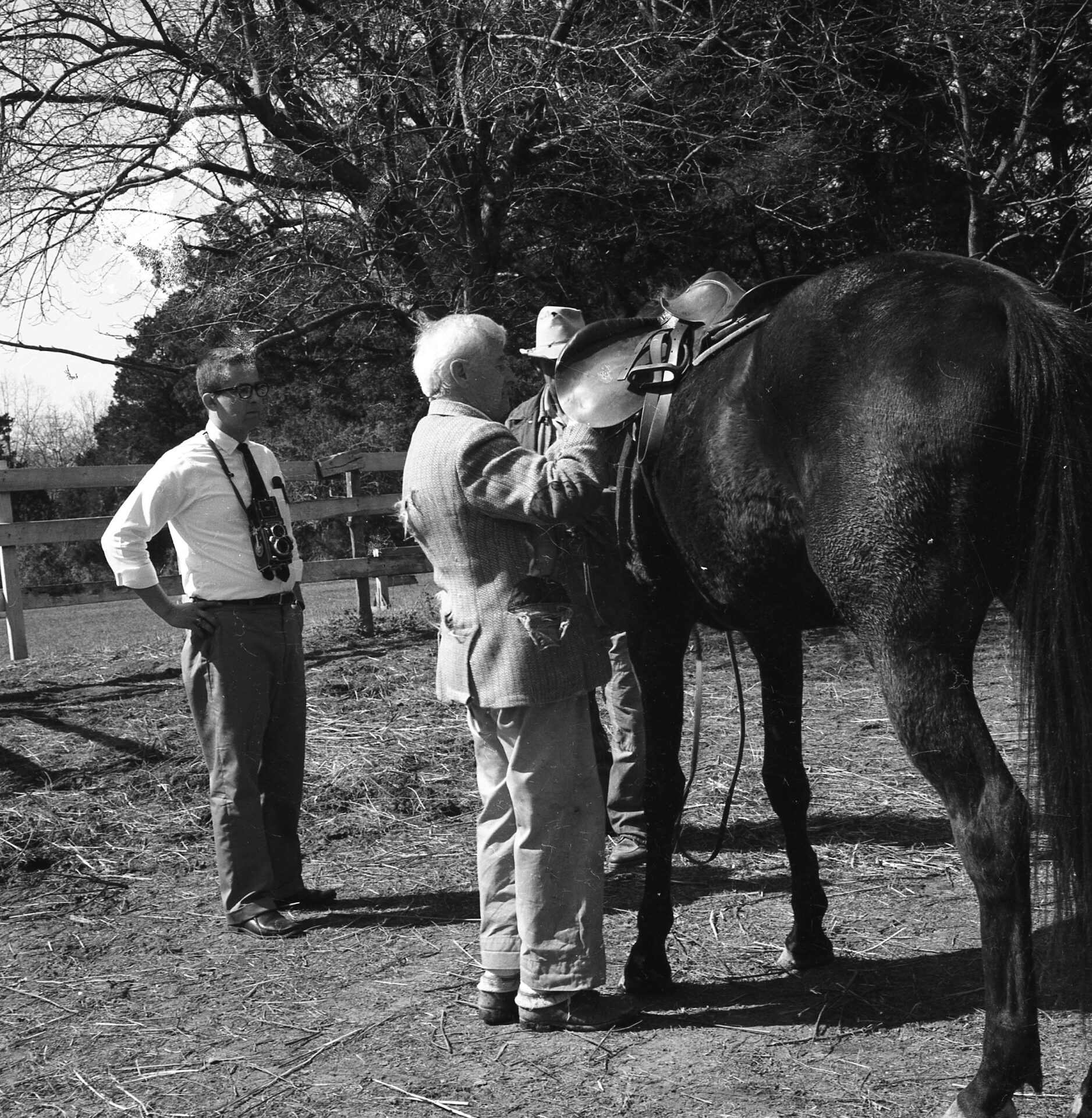

One of my early mentors was Col. J.R. Cofield, Mr. Faulkner’s family photographer for many years. Col. Cofield sort of adopted me, gave me the keys to his darkroom, and his son, Jack, and I became great friends. I was invited by Col. Cofield to observe Jack and the Colonel make what has become a famous portrait of Mr. Bill and to meet him in the Cofield studio. I quietly took many pictures of Mr. Bill while the portrait was being made, but these negatives, along with some of Mr. Faulkner riding his horses, were stolen from me.

Mr. Bill called Col. Cofield and wanted him to take pictures of him on his horses so he could send them to his daughter, Jill, who lived in Virginia. The Colonel did not have an outdoor camera so he turned the project over to Jack. Jack was horrified that he might screw up the pictures, so he turned the job over to me… and I screwed it up!

Jack and the Colonel cautioned me over and over to not take a single picture until Mr. Faulkner told me to do so. They really worked on me to make sure I did not violate their trust. I was known to be an aggressive young reporter, and they feared what I might do with this opportunity.

I was so anxious to take pictures of Mr. Bill, but I did what Colonel Cofield asked… almost. I did not take any pictures until Mr. Faulkner turned his back to me for the first time and I took the picture of him walking away toward Andrew Price, his handyman, who lived in the house out back. Although the first picture I took of Mr. Faulkner did not even show his face, I think that picture is the best picture I ever took. If you look carefully, before the picture was cropped, you could see that I took the picture through barbed wire. I was in the stable area across the fence when Mr. Bill went back to the house for something and I just could not stand it any longer, so I took that one picture

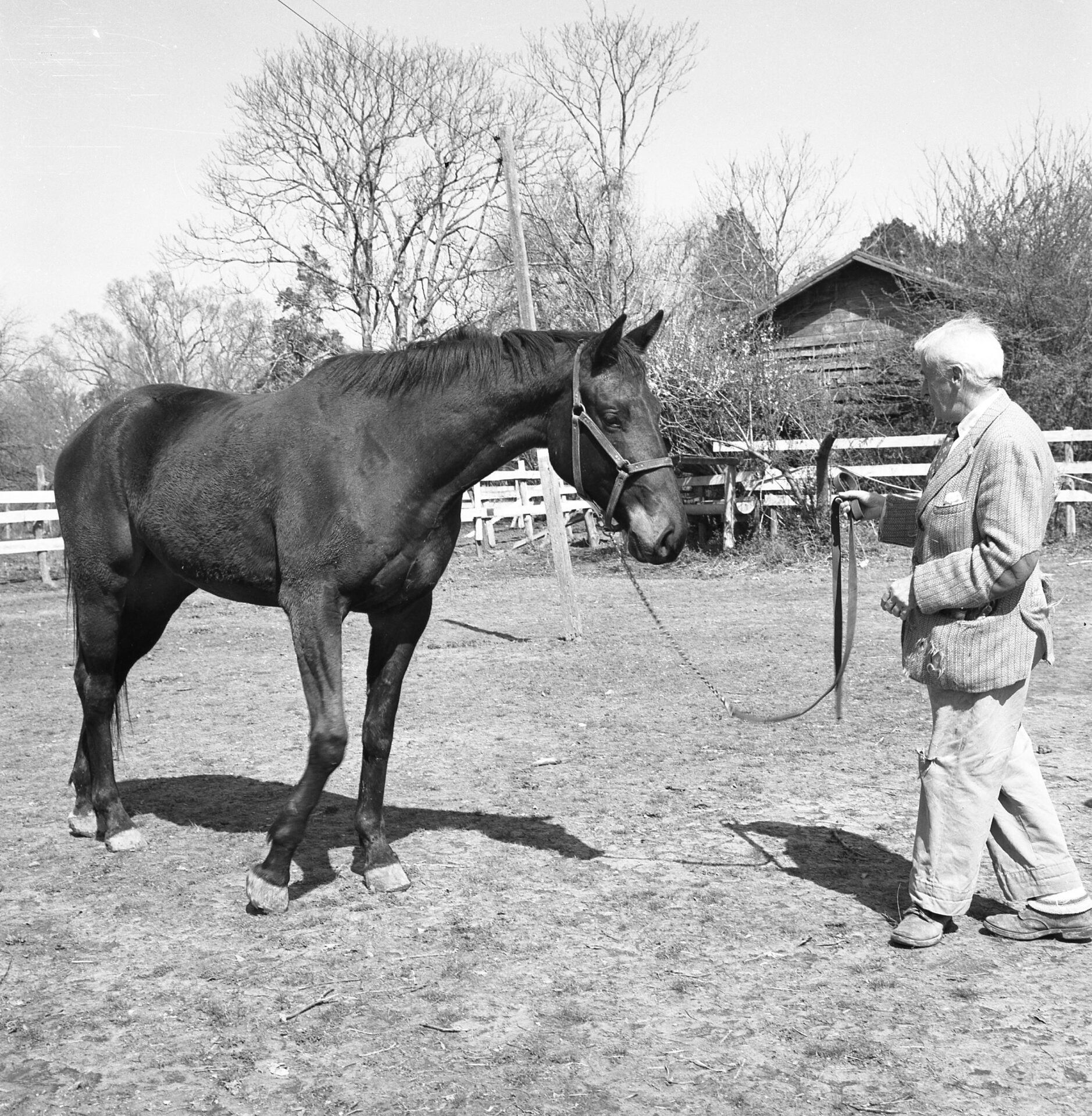

Mr. Bill got his horses from the stable and mounted the white one, who he said was named Stonewall Jackson. He told me his horses were jumpers and he would jump a row of hedges and I was to get pictures of him jumping. It was early August and blistering hot, but Mr. Bill had on the same tweed coat, despite the heat. He jumped with Stonewall Jackson a dozen times as I was positioned at the end of the row of hedges. He soon dismounted, came over to me, and asked, “Well, Mr. Meek, did you get some good ones?” He was wringing wet from the workout, red in the face, and I thought he was going to have a heart attack when I replied, “no, Mr. Faulkner, I was waiting for you to tell me to begin.” It was so hot and I could tell he just could not believe I had not taken any pictures. He climbed back on Stonewall Jackson, rode and jumped again, this time while I took pictures. The one shot of Mr. Bill riding Stonewall Jackson, tie flapping in the breeze and Mr. Bill up, out of the saddle (a no-no for a rider I learned years later, and clear confirmation that Mr. Bill was no horseman) is the other picture I treasure the most.

I went immediately to the darkroom and processed the pictures and gave proofs to Jack, who gave them to Col. Cofield for delivery to Mr. Bill. A couple of weeks went by and I had not heard from Mr. Bill, who was anxious to get the finished pictures. Finally, Col. Cofield called me and said there was a problem with the pictures and I needed to go see Mr. Bill.

When I arrived at Rowan Oak, Mr. Bill was standing under the west side porch in an old tweed coat with holes in it. He was standing in a bed of gravel relieving himself as I walked up. I was shocked, but he just smiled and asked if I “cared to join him”, explaining that Miss Estel, his wife, was having a tea party in the library, so head to go there. I declined. He finished, put his arm around my shoulder, and we walked toward his stable area.

When we came to a large stump that was in front of the log smokehouse, he stopped, pulled a handkerchief out of the sleeve of that old tweed coat, and asked if I had ever taken pictures of horses before. I assured him I had as Larry Speaks (who later became President Reagan’s press secretary) and I had taken pictures for pay at horseshows. Mr. Bill spread that dirty old handkerchief on the stump, took a pin, and drew a horse. He then handed me the pen and asked me to point out the most important part of a horse. With great confidence, I marked the head area, because that is where we always took the horseshow pictures, which showed the winners with their ribbons.

Mr. Bill took the pen and said, “I thought so. Mr. Meek, the most important part of a horse is the ass.” He took the pen and marked the rear of the horse. I had taken pictures from the front as Mr. Bill jumped over the hedge when I should have shot him from the rear. He told me he could not use the pictures and I told him I would be delighted to take them correctly. We agreed to another photo session.

He insisted he wanted to pay me for my work, but I refused because I had not done the job. He persisted and I did the unthinkable: I asked him to write a personal check for one dollar and sign it, or autograph a picture for me. He said “your choice”, so I told him I would bring a picture out for his signature.

A couple of days later, Mr. Bill was dead. He was drinking when Stonewall Jackson threw him and he was badly bruised. He was taken to the drying out place, as it was called, in Byhalia and ultimately fell down the stairs and died from combination of the fall and too much alcohol.

I never got paid for the job, but I was honored to have the opportunity to meet Mr. Bill and to be the last person to photograph him alive. He was exactly the opposite of what I expected. He was so kind to me, so warm and genuine, a true gentleman and he certainly was not the grump as I had been told. Mr. Bill seemed to enjoy me as much as I did him, even though I screwed up the most famous photo shoot of my life.

When I learned of his death, which was big news around the world, I sent a telegram to Life Magazine offering to send some of pictures. They paid me $2000 in advance and I sent proofs by air. Life did a major spread on Mr. Bill’s funeral and I was so excited to get that issue to look at my pictures inside. Life did not use a single picture, but I got to keep the advance, which was a great deal of money at the time.

After the funeral, I read The Bear, the first and only book I read by Mr. Bill. It was difficult for me to read, but it was like he was telling me the story, just Mr. Bill and me.

Kate Sinervo is an associate editor with HottyToddy.com and Ed Meek is the publisher. Meek took these photos.