Headlines

Traversing Pontchartrain: Memory and Movement Across the Busy Estuary

The Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain have shaped the cultural and economic development of southeastern Louisiana since early human settlements. The expansion of New Orleans and the North Shore means an ever-expanding network of transportation with thousands of people driving across Lake Pontchartrain each day. Others depend on the ships and trains traversing the lake to bring products into and out of the country.

The tolls, bridges and suburbs that now line the North Shore represent a large part of the area’s 21st century economy. Cypress forests and nearby estuaries originally surrounding Lake Pontchartrain illustrate the reason for original settlement: an abundance of seafood, plants and animals near a natural trade center. As people travel across and around the lake, they replicate patterns of migration that have occurred for thousands of years at the behest of the environment. As changing methods of transport accelerate travel between the North and South shores, people and environments become increasingly connected.

The south side of Lake Pontchartrain began forming 5,000 years ago as part of the St. Bernard Delta, a former distributary of the Mississippi River. The next 2,000 years brought more changes to the river’s course, with its modern eastern diversion to the Birdfoot Delta complex forming the remainder of the lake’s boundaries. By this point, groups of American Indians had constructed mounds along the big river and had also settled along the lakes and bayous formed between the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico. The lake provided a conduit to the river for trade via a portage through Bayou St. John, and early French explorers encountered Indians here in the 17th century as they also searched for an entrance to the Gulf.

Early Lake Travel

At the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Maritime Museum, volunteer Barry Knoess leads visitors on a tour detailing European settlement of the North and South shores. The museum sits near the confluence of Lake Pontchartrain with the Tchefuncte River in Madisonville, originally settled because of its convenient access to the lake and nearby timber forests. “The earliest French and Spanish settlers navigated the lake using sail boats, making travel upstream into the North Shore’s rivers difficult,” Knoess says. “The development of steam travel changed that, and towns like Madisonville and Covington began growing as steamboats transported agriculture and timber to New Orleans.”

Steamboats provided an opportunity for recreational travel, too. “It was a treat to go to New Orleans from Madisonville and stop to pick up passengers in Mandeville along the way. We landed at the West End, took a street car to Canal Street, and shopped,” says Enid Sims-Sears in an oral history at the museum. “You sucked on lemons if you got seasick. It was invigorating in an era of fewer diversions.”

During the Civil War, steamboats transported New Orleanians to the North Shore following their refusal to take the Union oath of citizenship. Yankee troops occupied the city for the majority of the conflict while residents of the Florida parishes remained Confederate. “The Civil War devastated the North Shore,” said Sims-Sears, “but eventually the steamboats and recovery returned.”

In addition to regular round trip steamboat rides, residents of either side of the lake increasingly looked to railways to traverse the water. The Pontchartrain Railroad carried travelers from New Orleans to nearby towns like Milneburg (now part of Gentilly) on the South Shore as early as 1830, but it wasn’t until 1884 that the New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad successfully sent the first train across the lake to Slidell.

“More people traveled back and forth over the lake and so did more products – timber, bricks, tar, cotton, sand and seafood,” says Knoess. “Shipbuilding was a key industry in Madisonville, and Covington was the head of navigation on the North Shore at the Bogue Falaya. Produce was grown there and shipped out, but it wasn’t the primary industry. Land on the North Shore was prime timber country: pine forests and clay earth.”

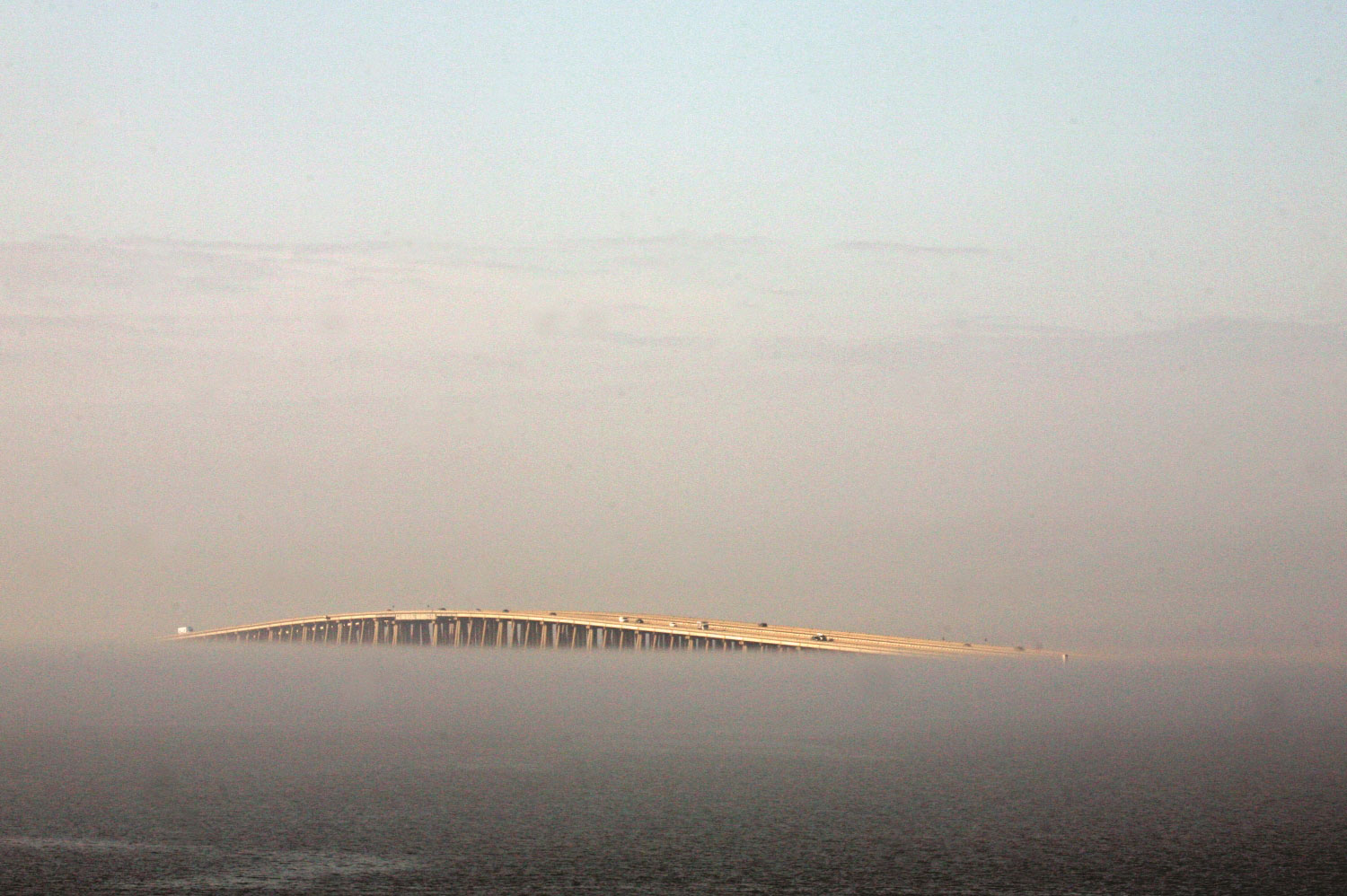

The World’s Longest Bridge

The first bridge to span part of the lake opened in 1928. Named the Watson-Williams Pontchartrain Bridge, it connected Slidell to the city but many residents of St. Tammany and Tangipahoa parishes continued driving around the lake or utilizing rail or steam to reach New Orleans. “It wasn’t until the 1940s that plans to build the Causeway began to come together.” says Catherine Campanella, a historian in New Orleans. “The bridge was originally a single span and opened in 1956.”

The Times Picayune reported that it took two gallons of gas to traverse the bridge and that construction was completed in 14 months. Photographs of opening day show cars lined up and down the causeway, waiting for a chance to drive from Metairie to Mandeville and back again. Bambi Engeran grew up on the North Shore with family in the city. “My parents took old Hammond Highway to get to my grandparent’s house in New Orleans,” she says. After they built the causeway, we would cross the bridge in my mother’s station wagon and my sisters and I would lie in the back and watch the stars at night driving back to the North Shore. Everyone loved that drive.

“When I was in high school the lakefront was the scene. We would drive to my aunt and uncle’s house in the city, and my uncle had a red Delta 88 Convertible with white leather interior. I would borrow his car and my girlfriends and I would drive three miles an hour for three hours, bumper to bumper along the lakefront on the South Shore. That was just what we did,” Engeran says.

The other novelty was to go to Pontchartrain Beach,” she says. “We drove from the North Shore but every family in New Orleans went, too. We always rode the Zephyr. It was the scariest roller coaster. There was also Lincoln Beach for black families. The beaches were segregated until 1964.”

The Causeway also increased traffic on the north of the lake, as ease of access combined with white flight and a growth in suburbs around the nation steadily increased the population north of Lake Pontchartrain. “When I was a little girl it only took a few minutes to travel from Mandeville to Lacombe and (after the bridge) we started having more traffic. It still wasn’t anything like it is today, though,” remembers Joyce Bates, a lifelong resident of Lacombe.

Economic development both in and out of the waters surrounding Lake Pontchartrain proceeded largely unabated until the passage of the Clean Air Act and burgeoning environmentalism in the 1970s. City officials closed Pontchartrain Beach to swimming in 1972 following the lake’s contamination from sewage runoff on the North Shore. “I remember when they closed the beach,” says Engeran. “I was too young to understand that the water was polluted.”

The estuary, known as Lake Pontchartrain, has a long history of travel. The earliest French and Spanish settlers used sailboats. By the early 19th century, steamboats made their way back and forth across the lake and aided in the development of Covington and Madisonville. It wasn’t until 1884 that the New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad successfully sent the first train across the lake to Slidell. The causeway made automobile travel across the lake possible in 1956. These days, travelers zip across the lake in minutes.

Photos courtesy John Snell, Legends Magazine

A Basin Rich with Artifacts and Stories

Michael Harley grew up in Mandeville and now lives in New Orleans. His parents owned Sweet Daddy’s restaurant on the North Shore while he was growing up. Before that, his father’s family of Houma and Creole ancestry lived and farmed in nearby Lacombe. “Lacombe is some of the last country still left on the North Shore because of the state park. When I was growing up, driving into Mandeville from the causeway was so dark. All you could see were lights at the end of docks as you drove into the North Shore. Now it looks like Metairie,” he says.

In Mandeville, the Causeway is used to give people directions, he said. “It’s always in the background like a skyline. You knew you had made it as a driver when you were confident enough to cross the bridge and make it into the city,” he says.

In high school, Harley and his buddies swam in the lake. “Right before I moved to New Orleans they tore up all the cypress forests … to build a parking lot for a new ferry system across the lake. Funding fell through and they never finished the project,” he says. “I’m glad that we have the causeway; it’s irreplaceable for people that live in that area of the North Shore, but I do worry about the future with so many people traveling back and forth and so much development of the forests and bayous.”

Lake Pontchartrain is 40 miles from west to east and 24 miles from north to south with boundaries traversing six parishes. Roughly 40,000 cars traverse its Causeway each day. A brackish estuary, it averages 12 to 14 feet in depth, “but in some spots it’s deeper than 50,” according to Engeran and other locals. The lake’s basin provides a home for millions of people, plants and animals. As commuters return to the North Shore after working in the city, pelicans search for dinner in the lake’s choppy waters and willow trees shade alligators waiting for nightfall along confluences of the lake to the rivers above it. It’s all connected.

Bridges, ferries and trains shorten the distance between people and communities, allowing for increased migration and economic development. The past has taught the people of the Pontchartrain Basin that development cannot be undertaken lightly – dredging, drilling and population growth have all negatively impacted the area’s plants and animals. The future requires a balance, connecting people and businesses on both sides of the lake while also acknowledging the fragility of southeast Louisiana and the importance of protecting its unique wonders. “The rivers and the lake are full of artifacts and stories,” Sims-Sears says, “traveling on our rivers and lakes keeps our stories alive.”

First published in Legends Magazine. Story by Meghan Holmes, photos by John Snell.