A historical investigation and commentary by Larry Wells.

“Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp,

Or what’s a heaven for?”

Robert Browning

The trouble with writing about a legend is that after awhile you start believing it.

Legends must be approached with caution. Each teller of a folktale embellishes, elaborates, embroiders until, kudzu-like, the legend creeps and entangles. Heroes become fabulous. New characters appear, phantoms who never were. A squad is a battalion, a ditch the Grand Canyon, a hill the continental divide. You know all this and yet…

Recently I traveled to west Tennessee and southern Germany tracking down a legend that I had written about. It kept coming at me in my sleep, long after my book was out of print.

My first novel, Rommel and the Rebel, was about the widespread belief that Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the “Desert Fox” of World War II fame, came to America before the war to study Confederate cavalry tactics, especially those of General Nathan Bedford Forrest. I based my version–my embellishment of the legend–on the published account of Lt. Colonel (ret.) Jack Maxey, of Jackson, Miss., that he and other military reservists hosted five German officers at Jackson’s Robert E. Lee Hotel prior to WWII. The Wehrmacht men were touring Civil War battlefields in Mississippi, primarily to see Brice’s Crossroads, where Forrest defeated a Federal force twice the size of his own. Maxey, who did not speak any German, later deduced that Rommel might have been among those officers.

This legend seduced many U.S. military men because after Rommel’s panzer-blitzkrieg drove through France in 1941 and gave the British 8th Army fits in North Africa, everybody, from strategists at the War Department down to combat tank commanders, wanted to know where the Desert Fox got his ideas.

When my novel was re-released last year, I began receiving reports of Rommel “sightings.” The director of the English-Speaking Union of America phoned to say that his father, a State Department official during the ‘Twenties, served as Rommel’s guide when he toured Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley before W.W.II. A judge in Pascagoula said he visited Rommel’s widow in Germany in 1955 and she told him that Rommel had stayed in Winchester, Va., during his Shenandoah trip and “did his banking there.” When the judge asked if Rommel was interested in the American Civil War, she took him into the field marshal’s study. Above Rommel’s desk was a portrait of Stonewall Jackson. Other stories surfaced of Rommel’s having visited battlefields in Vicksburg, Brice’s Crossroads, Shiloh, Trenton and Humboldt, Tennessee–of his giving a lecture at the Lee Chapel at Washington & Lee University!

I read everything I could find on the subject. A U.S. Army general had made extensive inquiries and concluded that the German officer wandering the Shenandoah battlefields was a Colonel Boetticher, military attache at the German embassy in Washington, D.C. Later, another military writer interviewed Frau Rommel and was told point-blank that her husband was never in America.

In Nashville this past fall, a Tennesseean told me, “Rommel was in Clifton, Ten. He came there to study Forrest’s river crossing. I’ve seen his name on a hotel register.”

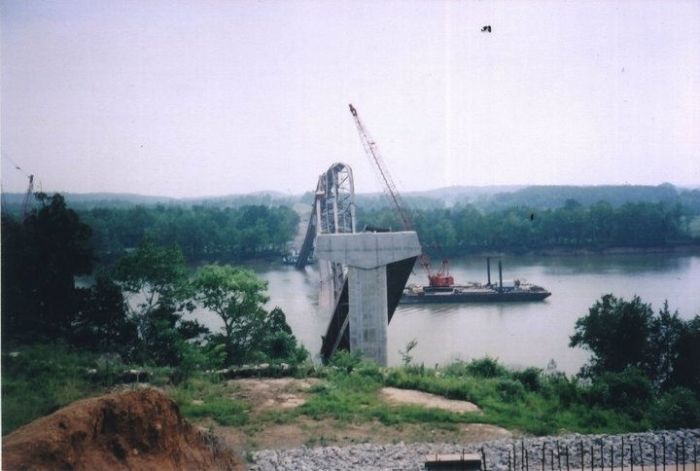

Clifton is a small town, population 750, perched on bluffs overlooking the Tennessee River a hundred miles southwest of Nashville. A flourishing place at the turn of the century, home to river boatmen and showboats featuring minstrel shows, the community has been hard-hit by the exodus of its young people who have gone to live in cities like Nashville, Memphis and Florence, Alabama. Its largest employer is a state prison housing some thousand inmates and operated by the Corrections Corporation of America.

Standing on Main Street and waiting for the occasional car to pass, I am beguiled by imagined echoes of minstrel banjo and shriek of steamboat whistle.

In my novel, a fictional Rommel visits award-winning author William Faulkner in Oxford, Mississippi. So I am amazed to learn that in Clifton, Rommel (a Wehrmacht captain in the early 1920s) reportedly visited novelist Thomas S. Stribling, who won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction (in 1933).

“Rommel sat right there on Stribling’s porch and talked about Forrest’s river crossing,” said a neighbor who has lived in Clifton all his life. (Is that a sly look in his eye, the look of an embroidering embellisher?) I am mesmerized by the empty porch swing, which moves ever so slightly in the breeze. I hear its chains creaking. From the Stribling lawn I can see where Forrest crossed the river. Rommel could have seen it, too.

I hear more about Rommel’s encounter with Stribling from Dr. Randy Cross (Ole Miss, Ph.D., 1975), Calhoun Community College English instructor and editor of T.S. Stribling’s posthumously published autobiography, Laughing Stock. “Mrs. Stribling told me,” said Cross, “one day, out of the blue, Rommel appeared, introduced himself and sat on their porch and chatted with Mr. and Mrs. Stribling. He told them he was following General Forrest’s route of march during his West Tennessee Campaign and asked them informed questions about Forrest’s movements and tactics. According to Mrs. Stribling, Rommel cut quite a dashing figure in Clifton. ‘All the girls were agog,’ she said.”

Stribling’s wife, Louella Kloss Stribling, the daughter of German immigrants, is said to have tried out her German on Rommel during his visit.

“They [the Striblings] both spoke fluent German,” Flora Mae Davis, 76, a columnist for the weekly Wayne County News, tells me, over fried catfish at Katie’s Kountry Kitchen. “I’m sure they had a lot to talk about.” Davis echoes the sentiments of other Clifton residents when she says, “Rommel was not like the others [Nazi soldiers]. I admire him so much. He’s the only German officer I admire.”

Flora Mae Davis said that Rommel stayed at the Russ Hotel, where a room and three meals a day cost one dollar in pre-Depression times. In later years, the hotel owner put a brass plaque on the door of a suite, calling it “The Rommel Room.”

The Russ Hotel, built in 1904, was razed in 1972. Today the lot where it stood is vacant and overgrown with weeds. Could a hotel register with Rommel’s signature on it be stored in someone’s attic?

“‘Fraid not,” says Wayne Country historian Ed Byler. “With the passage of time, any records of Rommel’s visit to Clifton have vanished, unfortunately, but I’ve heard accounts all my life that Rommel was here. He may have stayed up to two weeks, studying Forrest’s river crossing and troop movements.”

In December of 1862, Forrest built flatboats at Clifton, crossed the river and proceeded to attack Federal positions and supply depots in West Tennessee. After terrorizing Jackson, he rode north to Humboldt, Trenton and Union City, then turned south and met fierce resistance at the battle of Parker’s Crossroads. Attacked from the rear, Forrest pulled off one of the most daring maneuvers of the Civil War by sending a rear guard “charging both ways” while withdrawing his main force. Forrest later refloated his sunken flatboats and crossed the Tennessee River to safety while the citizens of Clifton waved Rebel flags and cheered.

I ride the Clifton ferry across the Tennessee River, sunlit and sparkling between brown clay bluffs and visualize Herr Hauptmann Rommel riding the same ferry (which has continuously been is in operation for over a century), contemplating in his mind’s eye Forrest’s men re-floating their submerged flatboats. I’m also experiencing an attack of double-deja vu. I am tracing Rommel’s path, whereas he reportedly snooped and sniffed after Mr. Forrest’s Rebel cavalry.

“My father was a mathematician,” Manfred Rommel told me, some months later in Stuttgart, Germany, where he served as Oberburgermeister for twenty years. Rommel, 65, a well-known national figure in his own right, received me in his office and graciously tolerated my obsession with his father’s travels.

LW: Was your father ever in America?

MR: No, he was not.

Mayor Rommel patiently listens as I recount my interview with Mrs. Carrie Willie Fowler, 82, who has lived in Clifton all her life. She is one of the few local citizens who remembers seeing Rommel. One reason the event sticks in her mind is that Rommel was riding the first motorcycle she had ever seen. “When you’re young and you see something like that for the first time,” Fowler told me, “you remember it. I was eleven years old and I had just walked out of my father’s store and was about to cross the street and here that man came, straddling his motorcycle.”

LW: In Clifton they remember the German visitor’s motorcycle, his jodhpurs and knee boots. It was that motorcycle, you see, that was the key! If disparate people in Mississippi and Tennessee both saw him on a motorcycle…

MR: Yes, my father was an old motorcycle driver. He went to Italy after the First War to see the battlefields where he fought, to make some tactical studies there in the Italian mountains. He went there not as a captain but as an “engineer.”

LW: Yes, yes, in my novel I have him traveling incognito, too!

MR: My father was never in the U.S. In war he was in Africa and France and Italy. In peace he went to Switzerland, Austria and also Norway.

I tell Herr Oberbergermeister Rommel about a news clipping dated Feb. 24, 1956, from the now-defunct Clifton Times, in which local resident J.I. Bell, a U.S. Army veteran who served in North Africa, recalled talking with a German POW who had been Rommel’s chauffeur. The POW told Bell that Rommel spoke often of his trip to Tennessee, saying, “If I could do with tanks what General Forrest did with horses, I would never lose a battle.”

LW: And so this J.I. Bell stopped the POW truck–mostly Afrika Korps men, interned near Tullahoma, Tennessee, doing road work, cutting weeds alongside the roads–and they stopped for water on Highway 64. One of the POWs saw the name “Clifton” on a road sign and he told Bell that in North Africa your father often spoke fondly of his trip to Tennessee!

MR: My father was never in your country.

LW: You were once quoted as saying your father was not very interested in literature.

MR: Not so much but he was very proud of me because I was interested. When anyone wanted to know where a quotation came from, I could in general say where to find it. He was proud of me, especially since this gift did not come from him. But he was a great mathematician. Before he died, when Gestapo were guarding our house, before he had to kill himself, he tried to explain calculus to me. He said this would open the way for me to higher mathematics. He said “You need only to listen for one hour and you will know it.” But after I listened about five minutes my father had to give up.

LW: And he was also a student of history?

MR: He knew all the dates of the significant events of history. He knew when an emperor was born or died, the Kings of England, of France. So he had a clear pattern of history into which to fix all he came to know.

LW: Did he study the American Civil War!

MR: It’s possible but I have no evidence of this.

LW: He is often compared to American cavalry generals!

MR: Yes, mobile warfare. The principles are the same. The fundamentals have been the same for hundreds of years.

LW: But some aspects of personality come into play, surely.

MR: Yeah, sure.

LW: For example, your father employed the tactics of surprise…”Shed sweat, not blood”!

MR: Yes and was permanently changing his plans. If he received reports in the night that showed he was wrong, he changed his plans in the morning. He saved a lot of blood.

LW: He outwitted the British in Africa!

MR: The British were well-trained but lacked flexibility, and their command structure was very complicated. If you read the British orders, they read like literature. My father developed a very simple wording for his orders, so if he changed the orders it was a simple matter.

LW: He had a sense of his own invulnerability…like Forrest!

MR: Yes, he believed he would survive. In France my father received a shell fragment in his face. In Africa he had a steel splinter stick in his belt, and at first he believed he was killed…but he was only green and blue in his belly.

LW: Both Forrest and your father had the heel of their boots shot off.

MR: I don’t remember that. A 35 milimeter shell once pierced his trunk [footlocker] and made a big hole in it. Maybe his heel was shot off and also his pants, his shirt, his underwear…

He laughs, a deep, rumbling laugh, and I smile, too, while legend pulses in my throat.

LW: Why do you think the story of your father’s coming to America persists? Is it the similarity between his tactics and those of Confederate cavalry?

MR: Military strategy is all the same. Even when it is bad.

He laughs again. I manage a weak grin.

I found that young people (under thirty) in Clifton, Tennessee, haven’t even heard about the mysterious German on the motorcycle, let alone know who the “Desert Fox” was. The name Rommel doesn’t ring a bell. World War Two is ancient history. And yet to some of the older citizens such as Flora Mae Davis and Carrie Willie Fowler (and to the occasional legend-seeker)indeed, to anyone with a reverence, not to say, a vulnerability for the pastClifton’s ghostly motorcyclist, whoever he was, anonymous wanderer or future war hero, lives on in their imaginations. They can still hear the rumble of his exhaust, the click of polished knee-boots as he bows to the Striblings, the rhythmic squeak of the porch swing, questions asked in Prussian-accented English, answers given in Southern-belle German.

LW: Could the ghost of Forrest, one wonders, have eavesdropped on that conversation?

MR: Mein Vater ist nie in Amerika gewesen.

Larry Wells is a frequent contributor to HottyToddy.com. This article originally appeared in The Oxford-American.